30 Theories of Cross-cultural Communication

Venecia Williams; Nia Sonja; and Verna Johnson

Comparing Cultural Frameworks

Researchers have developed cultural frameworks to help us understand how different societies shape communication, values, and social behaviour. These models offer insight into how cultural differences influence how people work, interact, and lead. While each framework focuses on different aspects, they all aim to explain the “below the surface” elements of culture—such as values, assumptions, and communication styles.

The following four frameworks are widely used in intercultural communication and business.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede, a social psychologist, studied how culture affects workplace values. Based on survey data from IBM employees across 30 countries, he identified six dimensions of national culture. These value dimensions influence how people communicate, lead, and collaborate.

Identity: Individualism vs. Collectivism

This dimension explores whether people see themselves primarily as individuals or as part of a group.

- Individualist cultures (e.g., Canada, U.S., Australia) value personal goals, independence, and direct communication.

- Collectivist cultures (e.g., many in Asia, Africa, and Latin America) emphasize group goals, social harmony, and loyalty.

These values shape leadership, feedback, and teamwork. For example, individualist workplaces may encourage open feedback and personal recognition, while collectivist ones may prioritize group cohesion and indirect communication.

Knowing where a culture leans on this dimension helps professionals better understand how to build trust, delegate tasks, and support collaboration.

Power Distance

Power distance refers to how people view authority and inequality.

- High power distance cultures expect clear hierarchies and respect for authority. Employees may be less likely to question leaders.

- Low power distance cultures prefer equality and open communication, with leaders acting more like team members.

Understanding this helps professionals adapt their leadership or collaboration style in different cultural contexts.

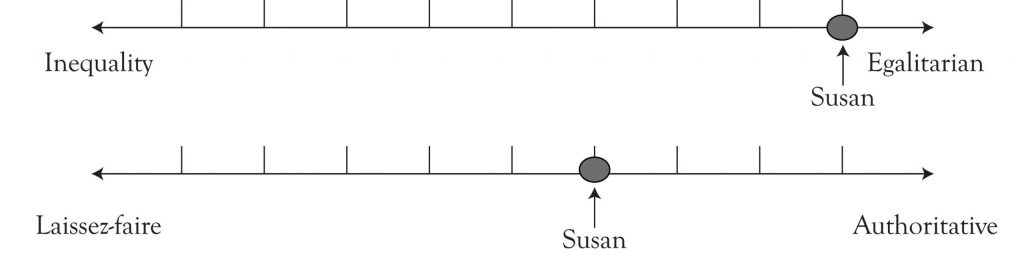

Let’s look at an example:

Scenario: Leadership Style

Susan is the president of a large manufacturing company. Even though she holds a position of power, she takes a hands-off, participatory approach to leadership. She encourages her employees to share ideas and voice concerns in meetings. This approach reflects a low power distance culture, where authority is balanced with openness and collaboration.

In contrast, in a high power distance organization, employees might expect Susan to make decisions without their input and see questioning her authority as disrespectful.

Understanding this dimension can help us adapt our communication and leadership styles when working in different cultural or international contexts.

Masculinity vs. Femininity

This dimension describes whether a culture emphasizes competition and achievement (masculine) or care and collaboration (feminine).

- Masculine cultures (e.g., Japan, Venezuela) value status, assertiveness, and material success.

- Feminine cultures (e.g., Sweden, Netherlands) value relationships, empathy, and work–life balance.

It’s not about individuals’ gender, but rather broad social values. A woman can thrive in a competitive culture; a man can prefer cooperation. The point is to recognize what the culture as a whole tends to prioritize.

This dimension can be considered a continuum, as illustrated in Figure 1.4, “Gender Dimensions.”

Masculine-Oriented Cultures

Focus on achievement, status, and success

Competition is valued

Roles between genders are more distinct

Success is often measured by material gain or advancement

Feminine-Oriented Cultures

Focus on collaboration, care, and well-being

Relationships and empathy are valued

Roles between genders are more fluid

Success is measured by quality of life and personal satisfaction

Understanding where a workplace or culture falls on this dimension can help you better navigate team dynamics, leadership expectations, and workplace values.

Uncertainty Avoidance

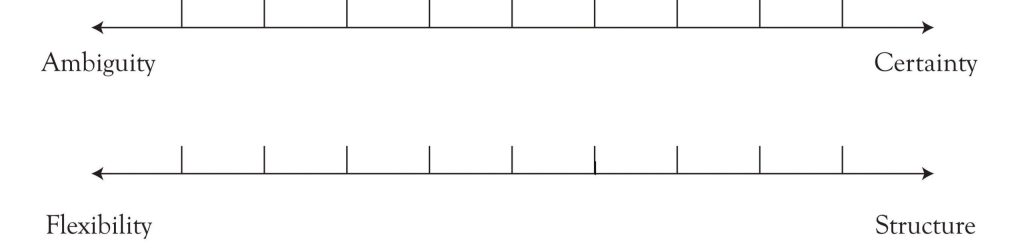

This dimension refers to how comfortable people are with ambiguity and change.

- High uncertainty avoidance cultures (e.g., Japan, Greece, France) prefer structure, rules, and predictability.

- Low uncertainty avoidance cultures (e.g., U.S., Singapore, Denmark) are more open to change, risk, and flexible approaches.

These preferences influence how people respond to innovation, conflict, or unclear expectations. In structured cultures, detailed plans build trust. In flexible cultures, informality may be more effective.

You can visualize this dimension as a continuum, as shown in Figure 4.5: Uncertainty Value Dimension.

High Uncertainty Avoidance

- Clear structure and procedures are expected.

- Change may be viewed as threatening.

- Risk-taking is limited.

- Conflict is often avoided.

- Precision and formality are emphasized.

Low Uncertainty Avoidance

- Flexibility and adaptability are valued.

- Rules may be interpreted more loosely.

- Change is more accepted.

- Innovation is encouraged.

- Open to new or ambiguous ideas.

This cultural value dimension is especially relevant in the workplace. For example, when working with colleagues or clients from high uncertainty avoidance cultures, providing detailed agendas, clear deadlines, and written expectations can help build trust. In low uncertainty avoidance settings, informal conversations and openness to new approaches may be more effective.

This dimension also speaks to a culture’s orientation toward directness and honesty. Anthropologist Edward T. Hall popularized the terms “high-context” and “low-context” culture to describe how societies differ in their styles of communication (Hall, 1981).

- High-context cultures are societies in which much of the communication is implicit. People rely on shared understandings, nonverbal cues, and the context of the interaction to convey meaning. Communication is often subtle and indirect. These cultures typically place a strong emphasis on group harmony and long-term, close relationships.

- Low-context cultures, on the other hand, tend to be explicit and direct. People are expected to say exactly what they mean, and written or verbal communication is usually detailed and precise. These societies often have many relationships, but they tend to be shorter in duration and less emotionally close.

Both communication styles are valid and effective, but misunderstandings can occur when people from different contexts interact. For example, a person from a low-context culture might view a high-context communicator as vague or evasive, while the high-context communicator might see the other as blunt or insensitive.

These differences are summarized in Table 2.3, “High and Low Context Culture Descriptors.”

Understanding both uncertainty avoidance and communication context can help you become a more effective communicator in multicultural environments.

Table 4.1: High and Low Context Culture Descriptors

| Cultural Context | Countries/Cultures | Descriptors | How They Perceive the Other Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Context | Spain | • Less verbally explicit communication • Implied meanings • Long-term relationships • Decisions and activities focus around personal, face-to-face relationships |

Low-context cultures are… • Relationship-avoidant • Too aggressive • Focused too much on tasks and goals |

| Mexico | |||

| Greece | |||

| Middle East | |||

| China | |||

| Japan | |||

| Korean | |||

| Thailand | |||

| Low Context | United States | • Rule-oriented • Knowledge is public and accessible • Short-term relationships • Task-centered |

High-context cultures… • Are too ambiguous • Are quiet and modest • Ask a lot of questions |

Time: Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation

This dimension explores how cultures view time and tradition.

- Long-term-oriented cultures emphasize perseverance, tradition, and future planning.

- Short-term-oriented cultures may prioritize immediate results and adapting to the present.

This also relates to how cultures balance tasks and relationships. For example, in some cultures, meetings start once everyone arrives—even if it’s later than scheduled—because relationships take precedence over punctuality.

For example, a business manager from Canada visiting India to negotiate a contract might expect the meeting to start on time and follow a tight agenda. However, in some parts of India, meetings begin once all participants arrive, even if that’s much later than the scheduled time. A Canadian manager who values punctuality as a sign of professionalism might feel frustrated in this situation. But for someone in a more relationship-oriented culture, being flexible with time allows space for connection and trust-building.

Neither approach is better or worse—they are simply different cultural values. Being aware of these differences can help professionals adapt and communicate more effectively across cultures.

See Figure 1.6, “Time Value Dimension,” for a visual representation of task-oriented vs. relationship-oriented time perspectives.

Indulgence vs Restraint

This dimension examines how freely people express desires and pursue enjoyment.

- Indulgent cultures (e.g., Mexico, Sweden, U.S.) value leisure, emotional expression, and personal happiness.

- Restrained cultures (e.g., Russia, Egypt, China) emphasize duty, self-control, and social norms.

These values influence work–life balance, communication style, and motivational factors in the workplace.

This dimension can influence:

-

Work–life balance: Indulgent cultures may promote taking time off, enjoying flexible schedules, and celebrating personal milestones. Restrained cultures may prioritize productivity, obligation, and professional boundaries.

-

Communication: People in indulgent cultures may express emotions more freely and use more informal language. In restrained cultures, emotional expression might be more limited, and communication may follow stricter social conventions.

-

Motivation: Indulgent cultures often focus on personal fulfillment and enjoyment as motivators. Restrained cultures may emphasize duty, conformity, or long-term goals over short-term pleasures.

Understanding this value dimension can help professionals better interpret workplace behaviours, motivational styles, and social norms across different cultures.

Trompenaars’ Seven Dimensions of Culture

Fons Trompenaars developed a model with seven dimensions focusing on relationships, time, and environment:

-

Universalism vs. Particularism – Are rules applied equally or adapted to context?

-

Individualism vs. Communitarianism – Are personal or group interests prioritized?

-

Specific vs. Diffuse – Are work and personal life separated or connected?

-

Neutral vs. Emotional – Are emotions hidden or openly expressed?

-

Achievement vs. Ascription – Is status earned or assigned?

-

Sequential vs. Synchronous Time – Is time linear or flexible?

-

Internal vs. Outer Direction – Do people seek to control their environment or adapt to it?

Like Hofstede, Trompenaars’ framework helps explain how values shape workplace behaviour.

High-Context and Low-Context Communication (Edward T. Hall)

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall introduced the concept of high-context and low-context cultures to describe communication styles.

- Low-context cultures (e.g., U.S., Germany) value clear, explicit communication. People assume less shared background knowledge, so information is explained directly.

- High-context cultures (e.g., Japan, China) rely on non-verbal cues, tone, and shared understanding. Communication is often indirect to preserve harmony.

These differences can cause misunderstandings. A low-context communicator may seem blunt; a high-context communicator may seem vague. Recognizing these differences improves cross-cultural communication.

Brett’s Cultural Prototypes: Dignity, Face, and Honour

Jeanne Brett (2014) identified three cultural prototypes that shape how people view self-worth, trust, and conflict:

- Dignity cultures (e.g., U.S., Northern Europe): Self-worth is internal. People value independence and directness.

- Face cultures (e.g., East Asia): Self-worth is tied to social harmony. Conflict is avoided to maintain reputation.

- Honour cultures (e.g., Latin America, Middle East): Self-worth depends on both internal pride and external respect. People may defend their honour strongly.

These prototypes help explain how people approach negotiation, disagreement, and relationship-building.

A Word of Caution

Cultural frameworks help identify patterns, but they don’t define individuals. Within every culture, people hold diverse views. Organizational culture, gender, ethnicity, and personal experience all shape how people communicate.

Use cultural frameworks as tools for understanding, not for stereotyping. With awareness and openness, we can build stronger, more respectful communication across culture

You can learn more about the different frameworks in the Culture section of Intercultural Business Communication.

Attribution

This chapter contains content adapted from Chapter 1.5 “Theories of Cross-Cultural Communication” in Fundamentals of Business Communication Revised (2022) (Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International) and Chapter 1.3 “Cultural Characteristics: Value Dimensions of Culture” in Intercultural Communication (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International).

References

References are at the end of this chapter.

Media Attributions

- Dimensions of Identity

- Power Value Dimension

- gender-dimension

- Uncertainty Value Dimension

- time-value-dimension