Fundamental to anti-oppressive social work praxis—the act of enacting, implementing or applying a form of practice—within Indigenous communities is to incorporate and implement a decolonized, trauma-informed, and culturally-safe framework. At the core of these frameworks are relationality and relational accountability. Throughout this chapter I will speak to praxis, rather than practice, as praxis is the intentional enactment of the frameworks (practice). An essential foundation of a dynamic social work praxis is to build relationships within Indigenous communities and with community members, while valuing and implementing the knowledge systems and values therein. As Indigenous or non-Indigenous social workers, the social work profession must examine how it has been colonially developed, and often maintains settler-colonial policy and practices; this approach devalues Indigenous sacredness of relationships. Comprehension of the historical manifestation of social work is imperative to prevent perpetuating colonial harm, alongside understanding the effects of colonization in rural and remote Indigenous communities. The views shared throughout this chapter must not be interpreted as a concrete blueprint for working within these communities, but rather, to underscore the importance of relationality with community and community members in social work practice.

The purpose of this chapter is to critically examine the history of social work in its relation to settler-colonial policies, to understand how our individual education, beliefs and worldviews may be informed by settler colonialism. While evaluating history, structures, and policies, we can critically examine our roles as social workers within rural and remote Indigenous communities, strive to develop meaningful relationships, and to integrate and establish our roles as helpers or co-creators, rather than as saviours.

The discussion of social work history and current policies can produce feelings of shame and discomfort. It is important to acknowledge these feelings, while working to understand the roots of these feelings, rather than resorting to offence and/or disregard. It is through this personal work that social workers can become co-creators, helpers, and allies.

The first part of this chapter will examine the history of settler colonialism and its roots within social work practice. Examining the roots of social work will provide context to understanding current and intergenerational trauma within Indigenous communities. Next, social work praxis will be explained through the importance of enacting an anti-oppressive practice, building relationships within community, cultural safety, decolonial praxis, and trauma-informed practice. The chapter will conclude with an explanation service delivery and connections to incorporating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into practice.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will have had the opportunity to:

- Understand the history of social work on Turtle Island (North America) and its current impact and implications within Indigenous communities;

- Evaluate our systems of knowledge, values, and experiences that form our own belief systems, including the ways that our settler worldviews impact our work in community;

- Understand the importance of relationships and relationality with and within community; and

- Understand anti-oppressive practice in order to actively implement culturally safe, decolonized, and trauma informed practice within rural and remote Indigenous communities.

History of Settler Colonialism in Social Work

To comprehend and contextualize social work praxis, the history of colonial, oppressive and assimilative policies that were implemented and carried out by social workers must be evaluated. Historically, settler-colonial ideology disregarded Indigenous ways of being and knowing, and legally prohibited Indigenous structures and living, such as hunting and gathering, family and community, governance, knowledge systems, spirituality and culture. Settler colonialism is different from other forms of colonialism, because it includes taking control of the land and all things in its domain (Tuck & Yang, 2012). Social workers were an essential element of the ongoing “assimilative policy projects” implemented by the government, which attempted to destroy Indigenous identities, families, communities, relationships, languages, and knowledge systems (Hart et al., 2010, p. 20), and carried out actions to maintain social control (Pugh & Cheers, 2010).

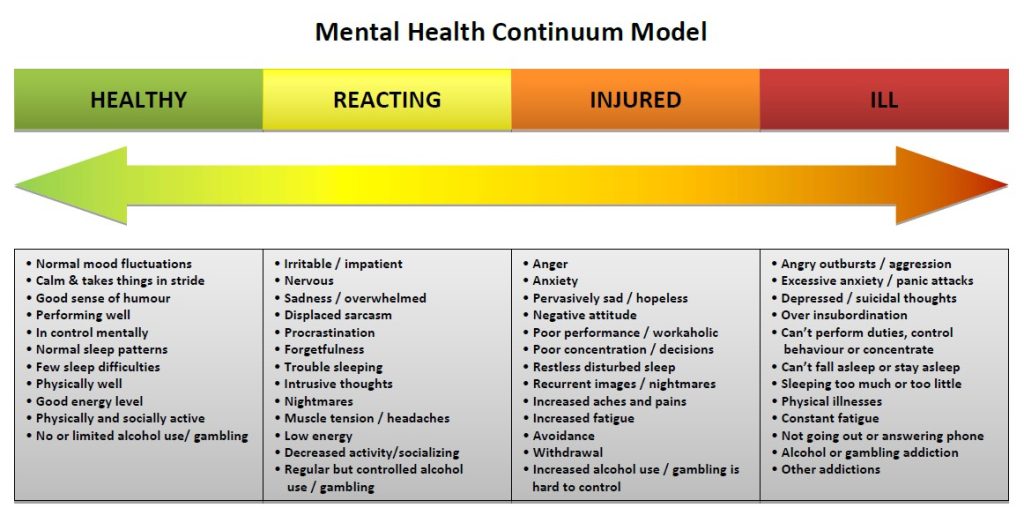

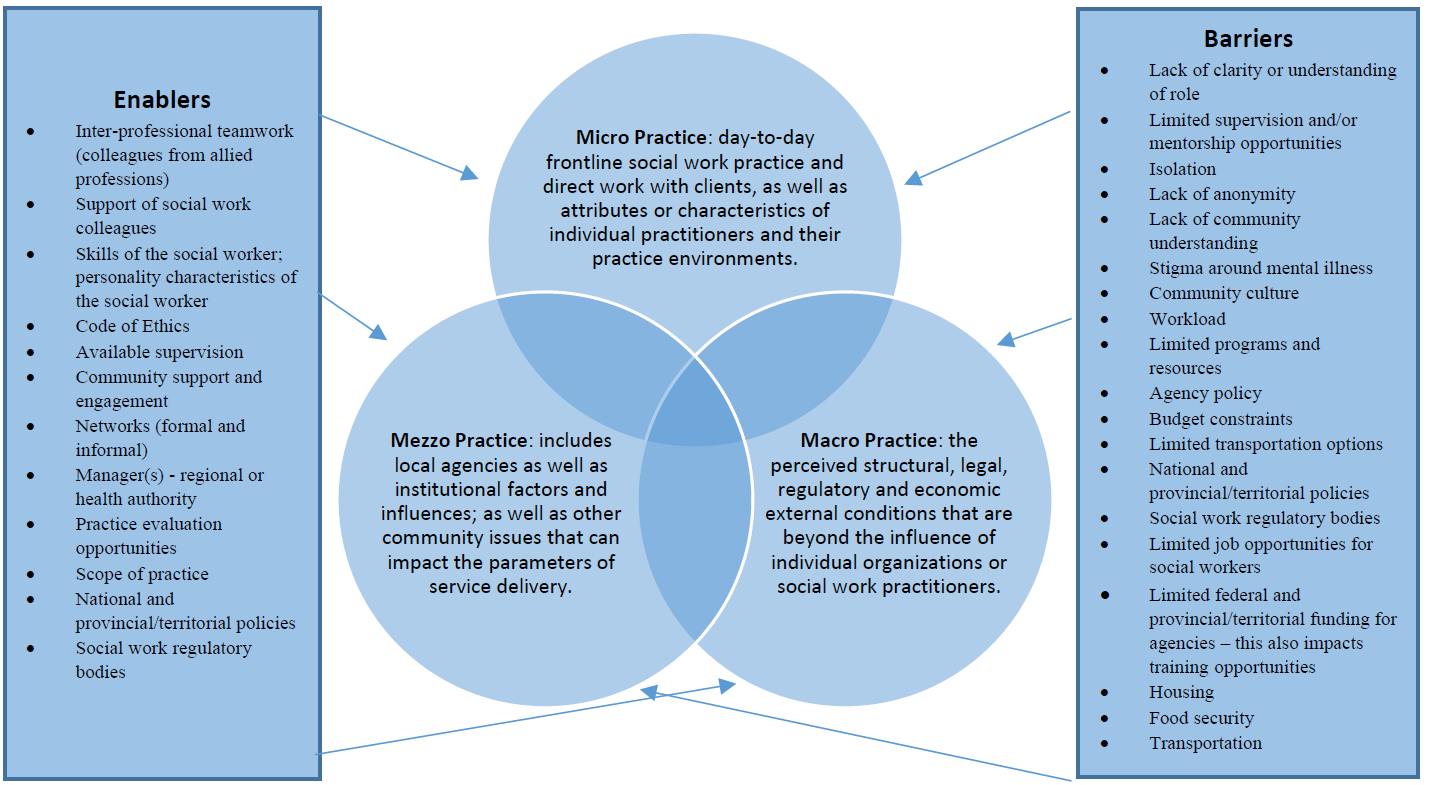

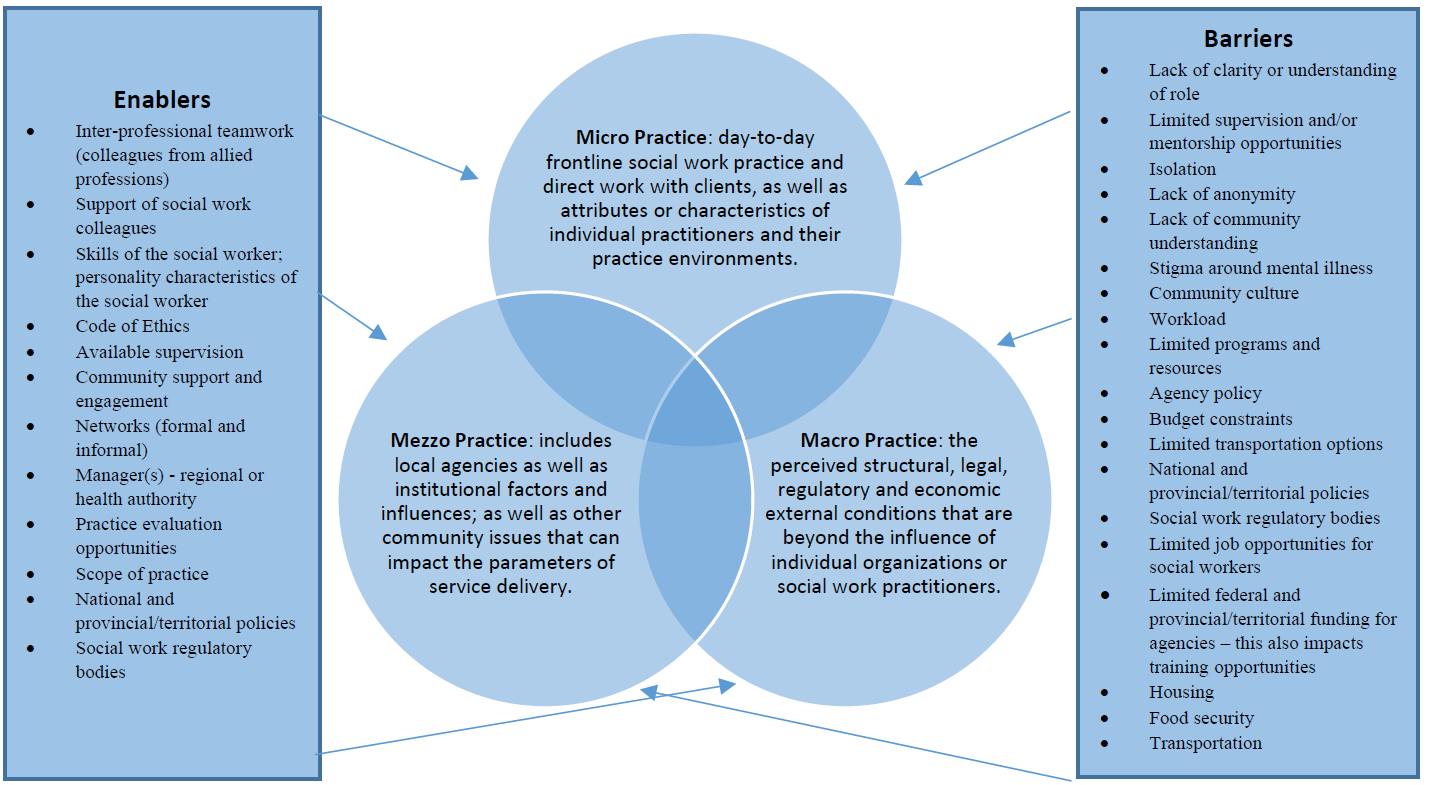

In the context of micro, mezzo and macro practice, many Indigenous worldviews identify that systems of individual, community, and nation are inseparable, and are interrelated within the understanding of wellbeing and kinship. Policies, legislation, and legally-binding documents were established, such as the treaties, the Constitution Act (1867), and the Indian Act (1876), to dismantle and extinguish Indigenous identities (micro), families and communities (mezzo), and Indigenous structures, systems, and governance (macro) (Greenwood et al., 2017).

The attempt to extinguish Indigenous identity (micro) included prohibiting spiritual and cultural practices, speaking Indigenous languages (such as within the Indian Residential School (IRS) system), and changing Indigenous names to more white-colonizer sounding names through treaties and residential schools, as residential “schools were attempting to make “little white children out of little red children”.” (Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006, p. 2). Settler-colonial ideologies of a superior race (white), or the notion to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man” (Pratt, 1892), have profound effects on Indigenous identity, which can lead to internalized colonialism (Bleau & Dhanoa, 2021). Internalized colonialism and denying Indigeneity, or ties to Indigenous background, can be maintained intergenerationally through family as a protection from alienation and ostracism from mainstream society.

Family and community systems (mezzo) were broken and legally separated through forced assimilation, including mandatory attendance at Indian Residential Schools (IRS), and the forced removal of children from their families, and illegal adoptions, during the Sixties Scoop. It was believed that removing Indigenous children from their families would rid Indigenous communities of their traditional ways and languages—referred to as “savage”—in order to assimilate Indigenous children into a “higher race” of the “English-speaking and civilized” (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, 1892). Approximately 150,000 children attended Indian Residential Schools (IRS) from 1870 through the 1990s (Walker, 2015). In 1892, Richard H. Pratt, founder and superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, stated:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man. (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, 1892)

Pratt’s ideology fueled the disregard for Indigenous life. The death rate of Indigenous children in Residential Schools itself is considered an act of genocide, with some schools having a death rate of 40% (Truth Commission into Genocide in Canada, 2001). Indian Hospitals targeted individuals and performed illegal / abusive medical procedures, including sterilization of women and girls, often without pain medication (Truth Commission into Genocide in Canada, 2001).

Under the Indian Act (1876) Indigenous systems (macro) were dismissed or legally prohibited, such as systems of governance, cultures, and ceremonies, and the forced and mandatory relocation to reserves. Some policies could be considered imprisonment, such as the Pass System, which prohibited Indigenous individuals from leaving the reservation without a legal “pass” from an Indian agent (Johnson, 2020). Individuals could be incarcerated for leaving reservations, even for survival purposes, such as hunting, fishing and gathering, or visiting with relatives (Johnson, 2020). Reservations could be viewed as mass prisons, which were controlled through Indian Agent surveillance.

The settler colonialism that occurred within Turtle Island (North America) was genocide, resulting in the extinction of over 90% of some populations (Greenwood et al., 2017). Indigenous people were viewed as unworthy of occupying space, as Pratt states “they occupy so much more space than they are entitled to either by numbers or worth” (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, 1892). Indigenous people were viewed as weak by colonizers, and it was assumed that Indigenous people would become extinct or fully assimilated (Greenwood et al., 2017; Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Greenwood et al. (2017) state that colonizers viewed Indigenous people as inherently weak and prone to sickness and therefore policies were implemented to reflect a paternalistic “protection.” Robidoux and Mason (2017) assert that settler-colonial control was justified by colonizers, because the ideology of success was associated with mass production, profit, and thus power. Indigenous ways of being and living, such as communal hunting, fishing, gathering, and equitable sharing lacked the basis of mass agricultural production and did not conform to the principles of capitalism. Pratt stated that he believed Indigenous people lacked the ability to exploit the land for their own use, which he viewed as foolish (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, 1892). For this reason, Indigenous ways of living were not highly valued, and thus directed by settler-colonial policies; Indigenous Nations were forced to farm, rather than to hunt and gather.

Indigenous people were robbed of their Indigeneity, land, culture, traditions, language and kinships in the name of colonialism and capitalism. These injustices stripped Indigenous peoples of the ability to exercise their autonomy to suit their own needs and interests (UNDRIP, 2008).

Settler Colonialism roots in Social Work

Social workers have been historically complicit in the unjust treatment of Indigenous people, as they played an active role in the kidnapping of Indigenous children for both Indian Residential Schools (IRS) and the Sixties Scoop. Social workers accompanied Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers to seize Indigenous children from their families. This act of illegally displacing Indigenous children continued into the era of the Sixties Scoop, where Indigenous children were fostered by, or adopted into, non-Indigenous families. As viewed through settler-colonial ideologies, which formed the profession of social work, Indigenous people and families were perceived as a “problem,” who could be “saved” from their “dysfunctional” selves, families, and communities (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2001). Indigenous people were also viewed as “savages” who were captive to their nation’s / tribe’s “savage language, superstition, and life” (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction, 1892).

Assimilation policies and colonial violence have led to a widespread Indigenous distrust of the government and those who occupy “white” government agencies (Pugh & Cheers, 2010). The historical policies and proceedings continue to carry deeply ingrained colonial and systematic forms of oppression which have continued the displacement of children into child welfare systems—constructing a pipeline to prison—and exacerbated psychological trauma and physical illness (Hart et. al., 2010; Johnson, 2020; TRC, 2015).

Fortier and Wong (2018) state that social work and the implementation of social services has “been created out of the trauma of dispossession,” which discounts Indigenous systems and knowledges and instead “work[s] with the more muted goals of alleviating the worst suffering while consciously or unconsciously supporting the ongoing process of dispossession” (p. 444). Thomas and Green (2020) encourage us to ask ourselves, as social workers, how historical oppression, assimilation and genocide contributes to community members’ perceptions of, and comfort with, social workers. They note that if a social worker were to ask an Indigenous community member or a family, “What is a social worker?” and “How would your ancestor answer this question?” (Thomas & Green, 2020, p. 92), the response might be shaped by personal worldviews and historical betrayal. We must recognize how and why social work was implemented in Indigenous communities, embodied as saviourism, in order to dismantle and deconstruct our understandings of social work with Indigenous people and within Indigenous communities. Once this is recognized, we can then re-create our roles as helpers and healers in community.

Rural and Remote Indigenous Community Practice

Rural and remote communities lie outside cities, and often have less access to resources and services, such as those associated with health and education. Rural communities are defined as having a population of fewer than 1,000 people living outside urban areas (Statistics Canada, 2018). Rural has been described as a physical place, climate, and economy; its resulting social context is regarded as remote or isolated, with sparse populations and limited services (Pugh & Cheers, 2010; Schmidt, 2010). However, Martinez-Brawley (2000) has recommended referring to these areas as “small communities” rather than specifically defining and labeling these areas as rural.

Collier (1984; 1993; 2006) states that “rural” is colonially defined, and has been used to name the places that Indigenous people occupy, which are often less valued spaces. Specifically for Indigenous people, the concept has been developed and based on settler-colonial standards and decisions of forceful creation of space, borders and determining resources (Pugh & Cheers, 2010; Schmidt, 2010). Rural areas that Indigenous people occupy, such as reserves which account for approximately 0.2 – 0.4 percent of land in Canada, are often utilized for resource extraction, such as through placing pipelines, that have adverse effects on health and wellbeing (Joseph, 2018; Kestler-D’Amours & O’Toole, 2019).

The lack of community resources for coping with these adverse health effects on rural communities will be discussed later in this chapter. Pugh and Cheers (2010), and Schmidt (2010) define rural as an understanding of the lack of resources available in that community. Lack of resources that are often available within cities or urban areas, may include health care (hospitals, nurses and doctors), education, mental health supports and services, substance use and harm reduction services, courts or probation offices, offices for social development (license, identification, health care documentation), grocery stores, and more.

Comprehending rural social work praxis through an anti-oppressive practice lens also includes understanding how rurality has been created and defined. Schmidt (2010) refers to Collier (1984; 1993; 2006) when speaking about the history of social work, stating that social work functioned to moderate capitalism and preserve the status quo by maintaining a certain dynamic of power and control within rural communities. Social workers must understand the current realities and inequities found in rural areas and small communities by knowing that these communities are a product of settler colonialism through exploitation and underdevelopment, leading to the elitism of settlers (Zapf, 1985). Elitism was created by utilizing government entities, such as Indian agents, and later, social workers, to direct Indigenous people and restrict them. For example, government administrations intentionally restricted Indigenous people’s access to food, such as attempting to eliminate the buffalo, followed by implementing government “policies that ensured failure rather than encouraged success” (Bateman, 1996, p. 12). Indigenous people were forced to live on reservations, which were intentionally placed on lands that were deemed unsuitable for sustainable farming (Bateman, 1996). Inadequate farming equipment was distributed to Indigenous people, compared to that of the neighbouring settlers, who were actually allotted land well-suited for farming (Bateman, 1996).

Social workers historically preserved elitism, by:

Promoting the potential development of one set of people at the expense of another set of people (elitism); that suggest that one set of people have greater human potential than another set of people (gender, racial inequality) or that deny that one or more set of people have human potential (oppression, slavery). (Delaney, 2009, p. 18).

The continuation of “relief” food was preserved through the work of social workers, continuing restrictive practices and promoting dependence on the government rather than encouraging sustainability and community development (Fortier & Wong, 2018).

Social Work in Rural and Remote Communities

Instead of replicating social work practice and service patterns that are common within other geographical areas, such as cities and urban areas, social workers must consider the history of ruralism and the unique needs of these communities (Pugh & Cheers, 2010). This shift can be achieved through both a culturally-safe framework and a generalist social work practice approach. Generalist social work practice involves remaining “skilled in working with individuals, families, small groups, organizations and communities” (Locke & Winship, 2005, p. 6) while also having a role as a resource navigator. For example, to combat the lack of resources, some Indigenous communities in British Columbia have resourced groups, such as Wellbriety, which deliver group counselling sessions while also integrating capacity building and resource navigation, such as equipping community members with harm reduction training and supplies. Other resource navigation approaches involve advocating for community members to have equitable access to resources, through video or Telehealth calls to health care workers such as nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, or courts and probation services.

A generalist practice approach is helpful within rural areas or small communities because social workers have many roles, which requires the ability to be multifaceted or versatile in order to meet the needs of the community member. As a social work colleague stated to me: “We work with whatever needs people have when they walk through the door” rather than engaging in a singular role (J. Kent, personal communication, February 2019). In restricting social work to a singular, specialized role or approach within rural communities, community members’ needs are not met. For example, some rural communities lack specific A&D workers (alcohol and drug workers). A social worker may not have the precise skillset or knowledge to complete addictions treatment applications with a client but is still considered “qualified” to fill that role. It is important to be adaptable and “general” or broad in being flexible in learning various skillsets or applications/assessments, so that community members are able to access appropriate services.

Anti-Oppressive Education & Practice

Rural Indigenous communities, which include reservations, were created to control, segregate, displace and oppress Indigenous people. Anti-oppressive practice acknowledges the historical injustices that have occurred, and actively works to prevent further harms from occurring. This section reviews historical forms of oppression, while evaluating how education is often dominated by settler-colonial views. It also explores fundamental elements of anti-oppressive practice, including the role of building relationships, cultural safety, decolonial praxis and trauma-informed practice. It is imperative to understand the importance of these unique practices, as they all uphold anti-oppressive values. Anti-oppressive practice is achieved by listening to, and implementing, the ways in which individuals and communities envision their healing, without overriding their decisions with one’s own personal biases or worldviews. Part of this process is to implement Two-eyed Seeing (Western and Indigenous healing methods and ideologies), rather than strictly encouraging colonial therapies and pathologizing, or “diagnosing” Indigenous experiences. Two-eyed Seeing incorporates both Indigenous and settler-colonial knowledge. Greenwood et al. (2017) describe Two-eyed Seeing as “walking into two worlds” and recognizing the strengths of both Indigenous and settler knowledge systems (p. 183). Social workers can engage in anti-oppressive and decolonized practice by invoking community members’ ideas for individual healing, as well as program and workshop development, while also resourcing decolonized therapeutic interventions, rather than resorting to mainstream evidence-based practices, which often fail to understand Indigenous ideology and cultural safety.

Anti-Oppressive Practice and Settler-Colonial Education

It is important to examine how our pre-conceived notions or indoctrinations, that are a result of the systems in which we live and work, are maintained by systems of settler colonialism. As a social worker within a colonially dominant culture, I recognize many social workers have been indoctrinated in colonially-developed education systems that tailor intellect in order to fit into mainstream practice (Johnson, 2020; Linklater, 2016). Johnson (2020) states that students (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) are taught to exclude diverse knowledge systems, such as Indigenous knowledges, and instead are persuaded “to think like a settler” (p. 39). Maracle (1996) states that “the appropriation of knowledge, its distortion and, in some cases, its destruction, was vital to the colonial process” (p. 89). The settler-colonial assimilation process was intended to conform education to the cultural, social and political beliefs of the settler (Thomas & Green, 2020). It was a settler-colonial assumption that Indigenous epistemologies were inferior, which created internalized racism, and supported the settler agenda of domination and colonization (Thomas & Green, 2020).

Thus, we must examine how teachings and training influence our relationships within social work practice. It is important to challenge the settler-colonial paradigms that dominate education, including social work education, which reinforce “altered forms of consciousness” and often separate the head (cognition) and heart (feelings) (Thomas & Green, 2020, p. 43). Settler-colonial education training is often objective, with the direction to assess, recommend, and implement (Thomas & Green, 2020). Many Indigenous traditional paradigms refer to relations and connections with family, community and the land (Gaudet, 2017; Thomas & Green, 2020), as a base for teaching through learning, watching, listening and participating (Stiffarm, 1998). We must examine how we are trained to write case notes and documentation, and we should question whether those case notes are strengths-based and non-pathologizing. Are we acting and writing in a way that best supports the community member? Are we respecting Indigenous traditional teachings within social work practice (Thomas & Green, 2020)? In asking these questions, we can actively evaluate if the social work praxis follows anti-oppressive practice principles.

Anti-Oppressive Practice

The incorporation and implementation of a decolonized, trauma-informed, culturally-safe framework and relationship building is fundamental to anti-oppressive social work practice within Indigenous communities. These frameworks, and how they associate and complement each other, will be discussed more in depth in future sections. In adhering to anti-oppressive practice, certain terms and labels are altered within the body of this chapter, such as replacing the term “client” with “community members,” to diminish the power imbalance and hierarchy that the word “client” may carry. Thomas and Green (2020) state that anti-oppressive practice should include analyzing power differences, examining methods of helping and healing, and exploring who we are and how this practice affects our relationship with people who have been historically and contemporarily marginalized.

A settler-colonial mentality has held the belief that Indigenous peoples and communities need to adapt to settler life and heal and nurture themselves in an evidence-based, specific way. Part of anti-oppressive practice is developing unique plans and programs based on collaboration with the community member and larger community, and utilizing flexibility and creativity rather than prescribing an intervention based solely on clinical perspectives. Clinical perspectives are formed around settler-colonial ideologies and often apply a restrictive biomedical model. As such, it is important to use a client-centered and generalist approach, which recognizes social inequalities while being flexible and versatile in meeting community members’ needs. One way of practicing this may be through developing a holistic healing plan.

A holistic healing plan is flexible, fluid and non-pathologizing. It focuses on the goals of the community member, while also exploring strengths in themselves and their community. A holistic healing plan may include incorporating the medicine wheel to understand how an individual identifies their strengths and areas for improvement mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. However, it should not be assumed that every community uses the medicine wheel. In adhering to an anti-oppressive approach, a holistic healing plan needs to be led by, with, and for the community member, rather than pathologized and clinically created solely by the social worker. A healing plan may also incorporate Indigenous forms of healing and ceremony, although this should not be assumed or enforced based solely on a person’s Indigenous heritage.

Role of Building Relationships

Building relationships within community and with community members, while maintaining relational accountability, is a fundamental element of anti-oppressive practice, and a pillar of culturally-safe, trauma-informed, and decolonized practice. Wilson (2008) describes relational accountability as demonstrating and practicing respect, reciprocity and relationality (The three Rs). Building relationships is essential to establishing trust and respecting boundaries, and is a crucial element of the therapeutic relationship. Creating relationships with community members is a process, and not an inherent right; this must be earned. As previously mentioned, it is important to understand that the process of relationship building with community members can be affected by the trauma inflicted by settler-colonial structures such as health care and social services. Recognizing the historical reasons social workers are viewed as untrustworthy or unsafe is imperative in understanding how current safety is experienced (Greenwood et al., 2017).

When working as an Indigenous or non-Indigenous/settler person within a community that is not your own, it is essential to adapt social work practices by identifying oneself as a guest within the community, and not as an “essential” component. This practice is a part of relationship building, and may include disclosing personal information such as who you are, where you are from, what your cultural background is, how your family relates to Turtle Island, where you went to university/college, and why you are in the community. Sharing and discussing these aspects of self is a way to build relationship and dissolve some characteristics of colonial power dynamics, which can often create a hierarchy of power and control, rather than establishing a trusting, relational practice.

As previously discussed, part of relationship building includes placing oneself as a guest in the community, rather than exercising a role of power and hierarchy, while also sharing personal information in order to create the dynamic of relational social work practice. Community engagement and building relationships might be achieved by honouring/accepting invitations from community members for events, which may coincide with cultural protocol in some communities (Greenwood et al., 2017). Honouring the advice and knowledge of community Elders and knowledge keepers is also imperative in efforts to respectfully engage with community, and coincides with the three Rs by respecting traditional knowledge systems.

Schmidt (2010) notes that it is not uncommon for a rural or remote community to evaluate social workers’ behavior, intentions, personal interests, and groups the social worker is connected with, alongside making inquiries to the social worker that may be considered as “intrusive questions” (p. 12). When we continue to ask community members about their own lives, without disclosing some information about ourselves, it creates a division which is often hierarchical. From a decolonial, culturally-safe perspective, actively participating in relationship building requires relinquishing settler-colonial habits, such as hiding our personal identities as a form of safety, while continuing to analyze community members from a position of power.

Genuine, active listening and engagement are imperative to understanding how individuals envision their healing, through co-creating and recognizing Two-eyed Seeing, rather than imposing colonial therapies and pathologies. A co-creator is a helper who collaborates with community members on their wellness, rather than exclusively deciding and delegating how they should conduct their wellness. Schmidt (2010) recognizes that relationships within rural / small communities are unique because connection and integration with community members is more frequent. Establishing trusting relationships is an important part of forming thoughtful discussions. Genuine and thoughtful discussions are an important part of acting as a co-creator within community engagement, and implementing community members’ ideas for programming, workshops and decolonized therapeutic interventions; social workers should not resort to mainstream evidence-based practices, which often fail to understand Indigenous ideology and cultural safety.

Evidence-based practice in social work has been informed and developed by those with power, as a result of both global and local informational systems of science, positivist and rationalist practice (Beddoe, 2007; 2013). Evidence-based practice thus excludes Indigenous knowledges, and traditional relational approaches to treatment (Beddoe, 2007; 2013). For example, being on the land (in nature), speaking with Elders and knowledge keepers, harvesting and using traditional medicine, and being involved in traditional ceremony enhance physical/biological, mental, emotional and spiritual wellness. These approaches to wellness do not fit the scope of evidence-based practice, and instead settler-colonial therapies and medicines, often developed for and by non-Indigenous people, are recommended. Part of relationship building is to explore what the community member views as healing, which may include the Indigenous methods listed above.

Another aspect of relationship building is understanding role conflict. Schmidt (2010) speaks about the importance of understanding role conflict when building relationships within rural Indigenous communities, as “outsiders coming in” (social workers, non-community members) or “insider[s] coming back” (social workers, who are also community members), and the complexities that they may face (p. 13). Role conflict recognizes the possible difficulties of navigating the lack of anonymity and immersion into the rhythm of community (Schmidt, 2010).

Relationship building is hence a combination of understanding the power dynamics of being a guest in community, building genuine relationships, actively engaging with community, and respectfully understanding community protocol and expectations. Relationship building is imperative in safely and respectfully engaging with community members and with the larger community as a whole.

Cultural Safety

Cultural safety is necessary for practicing anti-oppressive social work within Indigenous communities because of the legacy of colonialism which has created inherent power imbalances. Cultural safety is different than cultural competence. Cultural competence is pan-Indigenous, presuming that all Indigenous nations / communities share the same systems of belief (Yeung, 2016). Cultural safety recognizes the power imbalance between the social worker and the community member, while evaluating the cultural expectations that define treatment and deem which traditions are honoured (Greenwood et al., 2017; Yeung, 2016). Cultural safety is thus a practice of “shifting focus to the experiences of the person receiving care” rather than relying on preconceived ideas or beliefs about a community or nation (Greenwood et al., 2017, p. 182).

Cultural safety prioritizes Indigenous sovereignty and challenges societal hierarchies while necessitating safe practice (Yeung, 2016). Blaikie (2009) states that cultural safety is necessary because of social work codes of ethics and standards of practice which neglect to acknowledge “contextual, cultural and political realities for Indigenous [people]” (p. 3). The characteristics of cultural safety include knowing the history of colonization and its implications within social work practice and society as a whole; adapting social work practice to be community-driven and delegated; following and respecting community protocol while also working with Elders; and working with rather than on Indigenous people, because Indigenous people are experts of their own lives (Kurtz, 2013).

Cultural safety includes adhering to Indigenous knowledge systems and methods of delivering services and understanding Two-eyed Seeing (Greenwood et al., 2017). Two-eyed Seeing dismantles the ideology that healing must be delivered through settler-colonial, evidence-based practices, which ignore and exclude Indigenous knowledge systems as valid, and instead allows the incorporation of both. Crystal Morris, Indigenous traditional medicine practitioner from the Splatsin (Secwepemc) and Tsartlip (WSanec) nations, describes the concept of two-eyed seeing as recognizing the importance of healing methods and herbs that are indigenous to Turtle Island, as well as those that have been introduced through colonialism, in order to support community members and their individualized healing effectively (Morris, 2021).

Two-eyed Seeing creates an ethical space of practice and cultural humility, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members and practitioners can establish a safe space for collaboration, creativity and inclusivity—to listen, understand and dream together—in order to move forward (Greenwood et al., 2017). Cultural humility acknowledges that, as practitioners, we commit to a lifelong journey of continued self-evaluation, reflection, and learning, so that we can understand ourselves and our practice (Greenwood et al., 2017). Cultural safety is a way of being both within community practice, and simultaneously in daily individual practices (Kurtz, 2013). Understanding these concepts of cultural safety upholds and respects that healing must be rooted in Indigenous knowledge and values in order to actively support the restoration and reclaiming of these knowledges (Greenwood et al., 2017).

Decolonial Praxis and Connection to Social Work Practice

Colonization is the forced domination and hierarchy that the colonizer creates over the colonized (Kelm, 1998). Social work was developed by settlers and is maintained through settler-colonial structures. Patrick Wolfe (2007) states that “alism is a structure and not an event” (p. 5), highlighting the continuation of colonialism within structures intended for healing, including social work. For this reason, within anti-oppressive practice, social workers must recognize the importance of decolonial praxis. The ambition of absolute decolonization includes prioritizing Indigenous sovereignty, land rights and self-determination (Gahman & Legault, 2017), including the structures intended for health and healing.

Decolonial praxis actively prioritizes Indigenous knowledges, practices, and traditions, and thus works to coincide with cultural safety. The process of decolonization involves challenging settler-colonial policies and systems, so that Indigenous people can “be informed agents of their own lives and healing journey” (Lu & Yuen, 2012, pg. 192). This means to encourage Indigenous sovereignty (decision making) and advocate for Indigenous rights. An example of this may be through challenging systems such as the criminal justice system and adhering to a probation order; for example: advocating for traditional systems of healing (attending a restorative justice healing circle, as a part of a probation order), rather than adhering to settler-colonial law (attending an anger management course as a part of a probation order). Sinclair (2004) affirms that decolonial praxis addresses the historical and current settler-colonial impacts that are maintained through “colonial culture and social suppression, intrusive and controlling legislation, industrial and residential school systems, the child welfare system, and institutional / systemic / individual racism and discrimination” (p. 76).

However, some practitioners, such as Fortier and Wong (2018), state that decolonizing social work is impossible, because the field was developed and is maintained by colonialism. Therefore, Fortier and Wong (2018), call for an unsettling of social work, through:

Deprofessionalization (the restructuring of the ‘helping’ practices of social work back under the control of communities themselves); deinstitutionalization (fighting against the non-profit industrial complex and re-focusing on mutual aid, treaty responsibilities, and settler complicity); and resisting settler extractivism (working towards the repatriation of land, children, and culture and the upholding of Indigenous sovereignty and resurgence). (p. 447)

Part of decolonial social work practice is examining ways in which social work may continue to perpetuate colonial harm. Tuck and Yang (2012) warn against settler harm reduction, which is the act of reducing the harms caused by settler-colonialism, but not seeking to give up privilege, power, and control exercised over Indigenous people and communities (Tuck & Yang, 2012). An example of settler harm reduction would be to focus on a person’s substance use (micro) as the root of their problem, rather than to evaluate the societal and historical impacts (macro) of colonialism, such as lack of housing, land, and resources. As Michelle Alexander (2020), a Black civil rights advocate, states: “we must not be seduced into believing that improving the system is the same as dismantling or transforming it” (p. xxxvii). Practicing this form of settler harm reduction is a method of settler-colonial innocence and continued compliance with the macro structures of colonialism (Tuck & Yang, 2012). Decolonial praxis is thus unsettling social work, rather than attempting to supplement or Indigenize social work (Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Trauma-Informed Practice

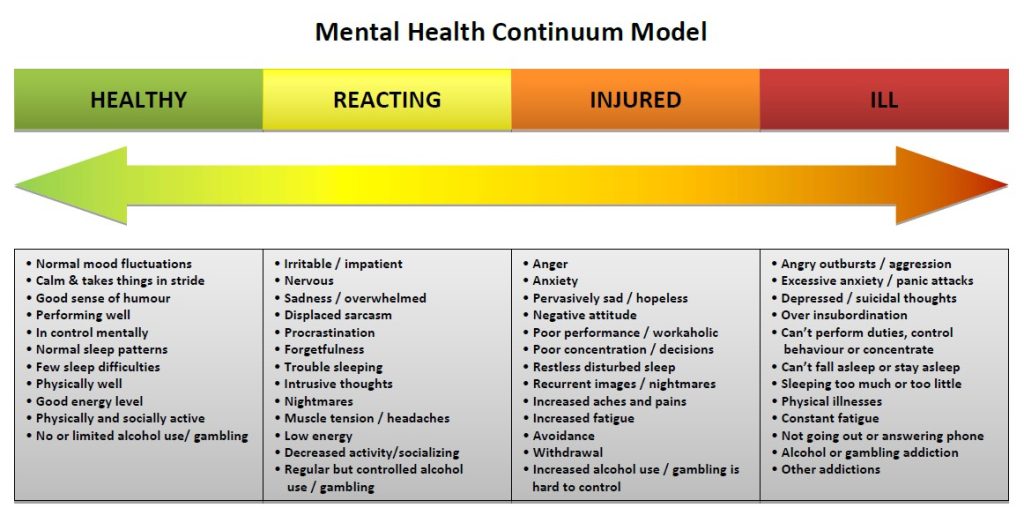

The term “trauma” has been created by settlers and has been used to diagnose and pathologize Indigenous experiences of pain and suffering (Linklater, 2016). Furthermore, colonialism is at the root of Indigenous trauma, and this element must be identified in order to take away the blame and shame of trauma from individuals and families (Linklater, 2016). Burstow (2003) describes trauma as “not a disorder but a reaction to a kind of wound” (p. 22). The impact of trauma should be considered interpersonally and intergenerationally, as well as understand the transmission of traumatic experiences and learned behaviours from previous generations. Trauma can affect a person’s (micro) and community’s (mezzo) holistic well-being, emotionally, physically, socially and spiritually, and can be maintained through settler-colonial structures (macro).

For social workers, trauma-informed practice is client-centered and includes being actively aware and conscious about how a community member has been harmed (mentally, emotionally, physically, spiritually) and perceives themselves and their safety in the world. Trauma symptoms, such as “arousal, attention, perception and emotion” can sustain “in altered and exaggerated states long after the specific danger is over” (O’Neill, 2005, p. 75). It is therefore important to acknowledge and recognize that a person’s experience of the present state can be impacted by the trauma they suffered from previously. Trauma-informed practice understands the individual impact of trauma, which is often a result of colonially-created systems (Linklater, 2016), and “strive[s] to provide programs and services which avoid retraumatizing people while supporting their movement towards resilience, recovery and wellness” (Randall & Haskell, 2013, p. 517).

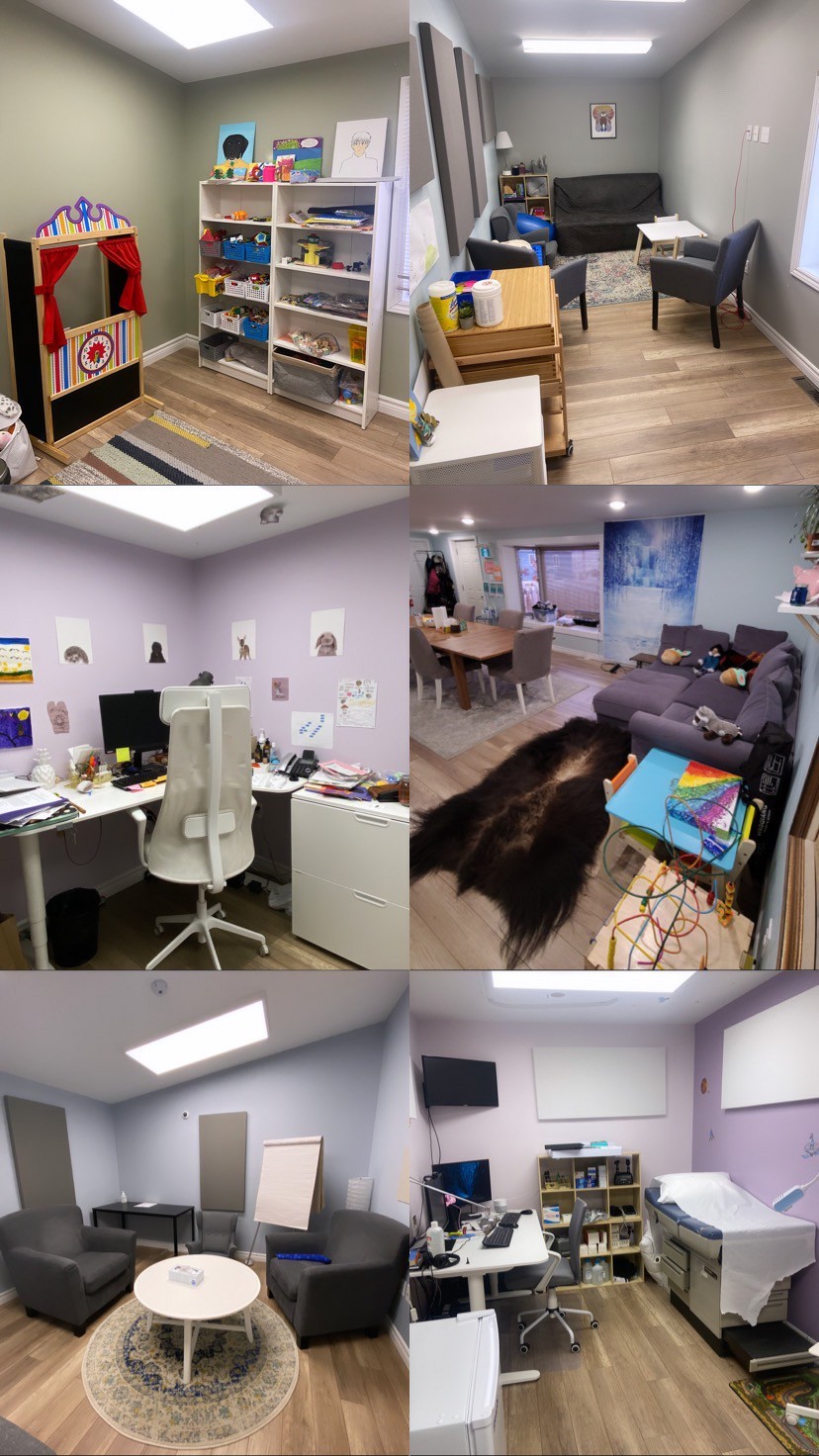

Fortier and Wong (2018) refer to Tuck and Yang (2015) when speaking about how social workers can unintentionally re-traumatize Indigenous people and that we, as social workers, “must recognize settler complicity in colonial violence” (p. 447), which can devalue the experiences of community members. Trauma-informed practice includes culturally-safe practice, recognizing the individual impacts that physical spaces (waiting rooms, offices) can have on a person, and can be perceived as violent or threatening. For example, hospitals and office-settings can resemble that of residential schools, and can cause an inherent visceral trauma reaction (Chansonneuve, 2005). Trauma can also endure through other physical settings such as classrooms, hospitals, and social service offices, which can be seen as unsafe (Brunzell et al., 2016; Perry, 2006). Therefore, being trauma-informed includes being actively engaged in dialogue, identifying the ways in which a person feels safe and in danger, and adapting social work praxis to suit the needs of the community member (client-centered).

Linklater (2016) explains that Indigenous people have experienced increased alienation and trauma when seeking help. It is important to create safe spaces and adjust environments to harmonize with a community member’s needs. An example of adapting spaces to feel safer can include adjusting office space, or practicing social work on the land (land-based). A social worker can engage in a conversation about what setting would make the community member feel more comfortable or safe, such as different lighting, or moving to a different location such as sitting outside. For example, a community member once informed me that the lighting in my office was too dark (it was winter, in the late afternoon and the lights were off in the centre, leaving the room shaded). Although explanations are never needed, the community member explained that they had experienced a traumatic experience in a shaded room. It is important to acknowledge these experiences and adapt the environment to the individual’s need. As previously mentioned, an individual’s or a community’s unique experiences can cause distinct reactions to trauma. Indigenous people and communities have survived settler-colonial attempts to extinguish and assimilate them (Greenwood et al., 2017). Trauma-informed practice recognizes the resilience of community members and communities, as well as unique forms of healing.

Policy and Service Delivery Issues

Settler-colonial policy and service delivery has historically failed to meet the needs of Indigenous individuals and communities. Linklater (2016) explains that these service delivery methods were not created from an Indigenous worldview. The creation of these systems, both within the confines of physical and political boundaries of Indigenous communities, limits relevant services (Pugh & Cheers, 2010; Schmidt, 2010).

Policy and Control

When treaties were first established, Indigenous people believed that their inherent right to traditional Indigenous systems and cultures would be continued and maintained (Robidoux & Mason, 2017). As previously mentioned, current social work practice in Indigenous communities is governed by settler-colonial policy. Although work to “Indigenize” programs and policies are underway—including healing lodges, sentencing circles, restorative justice, treatment centres and health centres—these programs are still maintained and controlled by colonial systems that delegate structure and provide funding, and thus cannot be fully independent (Giannetta, 2021). Giannetta (2021) articulates that the tactic of Indigenizing current colonial systems is a means to maintain power and control, without implementing any meaningful change. An example of this failure to dismantle settler-colonial policy can be seen through examining current healing lodges within the Justice system:

These lodges operate within penitentiaries (a colonial institution) after an Indigenous offender has been sentenced (through a colonial justice system) for committing a crime (defined by the colonial political system) caused by underlining social issues (stemming from colonialism). (Giannetta, 2021, p. 4)

Indigenous communities continue to strive to overcome these barriers through implementing grass roots programs and initiatives. For example, in British Columbia, the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) is an Indigenous-created and led health authority with the “commitment to engage and privilege Indigenous health and wellness” (Greenwood et al., 2017, p. 185). However, within FNHA programs, barriers of accessibility continue to be prevalent. For example, long wait times for admission to substance use treatment centers, which can be between 1 – 3 months, can be detrimental to healing. Furthermore, similar to non-FNHA treatment centers, many FNHA treatment centers do not support access to harm reduction services and deny the individual’s acceptance to programming if they access Opioid Agonist Therapies (OAT), such as suboxone, methadone or kadian. OAT is a longer-acting opioid that decreases withdrawal and minimizes cravings for individuals who use substances such as heroin, fentanyl and oxycodone. OAT is prescribed by medical professionals. These barriers can lead to sustained or increased use of substances, and overdose.

Delivery of Service

There is undoubtedly a lack of access to social, health and extended services in rural, remote and small Indigenous communities, because of the historical displacement of and disregard for Indigenous people and communities (Pugh & Cheers, 2010; Schmidt, 2010; Zapf, 2010). Some communities have adapted to the lack of services, for example, the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA), discussed in the previous section, has implemented access to virtual doctors, psychiatrists, addictions specialists and counsellors. However, to access these services, individuals need the internet, which is often unavailable in rural and remote areas, including on reservations and in Indigenous communities.

Further injustices leading to barriers are intensified due to resource extraction, and the “rape” of the land (Hunt & Craft, 2021). One example of this is the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which was originally planned for an area that could potentially affect the water system which serviced non-Indigenous communities (McKibben, 2016). The pipeline was moved to Indigenous land, without the consent of the Standing Rock Indigenous Nation (McKibben, 2016). When Indigenous people and communities voiced their concerns, they were ignored, which led to worldwide attention, and subsequent social justice movements. However, pipelines and resource extraction not only affect the physical health of Indigenous Nations, but they also create worker camps, which directly increase the potential for physical and sexual violence against Indigenous women and girls in surrounding nations, contributing to the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIW) (Hunt & Craft, 2021; Macy, 2020).

Barriers to service delivery are exacerbated by a lack of public transportation options, including the cancellation of bus service provided by the Greyhound bus company (Rodriguez, 2021). Access to fewer, or no, options for transportation affects individuals’ ability to access health services and appointments, education, employment and opportunities to meet and gather with family (Rodriguez, 2021). Transportation restrictions have led individuals to choose hitchhiking in order to access these services, which is a safety risk, especially for Indigenous people. The Trail of Tears is one horrific example of Indigenous peoples’ disproportionate risk, referring to a stretch of road where individuals have gone missing or been murdered while hitchhiking; again, increasing the number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIW) (Levin, 2016).

In order to cope with these barriers, some social work practitioners recommend community-based service delivery, which utilizes Indigenous community strengths, resources and natural helping systems. Zapf (2010) refers to Nelson (1986) when recommending a model of integration of services in various communities in both Canada and Australia. Some of the communities are interagency and include recreation, education, policing and other services that are within, or close to, rural communities (Zapf, 2010). Building on strengths, skills and abilities within the community allows members to access services more quickly.

Community-based service delivery can be enhanced by building capacity within these areas. The purpose of community capacity building is to educate, consult with and train local community helpers so that they can deliver services within that community (Zapf, 2010). Building local expertise and community confidence through natural and informal helping systems is less costly and sustains services in community (Zapf, 2010). Social workers are advised to support natural and informal support systems, and not to replace or supplant (Zapf, 2010). An example of capacity building in addictions services is identifying and supporting a community champion, who may, for instance, identify with having used substances, or is using, and acts as a provider of harm reduction supplies or participates in leading community action teams.

Other barriers to service delivery in community work can include rigid rules and regulations, from “a controlling power of the state” and “conflicting expectations of state, profession, employer, and community” (Zapf, 2010, p. 74). This refers to the power and influence that provincial and federal policy and regulations have on Indigenous communities, and the disregard of Indigenous autonomy. Zapf (2010) encourages social workers to navigate these barriers by dynamically interweaving creative flexibility and collaborating in decision making with the community. Zapf (2010) further explains that social work practice becomes “more intuitive, as the worker comes to rely more on community relationships and less on the authority of knowledge” (p. 75).

Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW) Code of Ethics

The values present within the CASW (2005) Code of Ethics that are distinct when working with rural / small Indigenous Communities include advocating for equitable services and challenging injustices [Value 2], which, as previously mentioned, are barriers when working within these communities. The CASW (2005) Code of Ethics states that social workers must understand the power imbalance that occurs in a social work-community member relationship, while prioritizing the needs of the individual [Value 3]. Value 3 (CASW, 2005) also states that a social worker should use their professional knowledge and skills when working with a community member. However, social workers must acknowledge the history of settler colonialism and engage in collaborating and implementing Indigenous knowledge systems and healing, as these pertain to the community/community member.

Registered social workers are accountable to the Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW, 2005), and the provincial/territorial associations and colleges, and are required to adhere to a standard of practice, ethics and values. An important focus in the CASW (2005) Code of Ethics, and stressed by Arges et. al. (2010), is that social workers have an obligation to uphold:

The welfare and self-realization of all people; the development and disciplined use of scientific and professional knowledge; the development of resources and skills to meet individual, group, national and international changing needs and aspirations; and the achievement of social justice for all. The profession has a particular interest in the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and/or living in poverty. (CASW, 2005, p. 3)

This statement is not particularly anti-oppressive in its wording, since it suggests that social workers can label and define who is considered vulnerable or oppressed, alongside highlighting the use of scientific and professional knowledge, rather than community and traditional knowledge. However, it nonetheless stresses the importance of upholding individual and community needs, and of social justice. This would suggest that the role of social workers is to work with, rather than on, community members.

The TRC and UNDRIP

The CASW (2005) Code of Ethics also mentions the importance of honoring the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Other relevant reports pertaining to Indigenous people, made by and for Indigenous people, include Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (TRC, 2015) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2008).

The TRC (2015) has created calls to action that specifically name and call upon social workers to be educated and trained when working with Indigenous communities, so that they will provide culturally-safe and “appropriate solutions to family healing” (p. 1). Other areas recognized in the TRC (2015) are the call for recognizing and valuing community-controlled Indigenous healing practices and working with Indigenous healers and Elders. Giannetta (2021) reflects on these elements when stating that systems of healing and being must be implemented, and not expected to “operate within the confines and to the discretion of” settler-colonial systems (p. 7).

Social workers should be educated about the implementation of UNDRIP and honour / abide by the Indigenous collective rights therein (Greenwood et al., 2017). UNDRIP (2008) calls for the restoration, reclamation and sharing of Indigenous knowledge of health, while also acknowledging the settler-colonial influences in “harmful systems, organizations and relationships” that perpetuate harm (Greenwood et al., 2017, p. 182). Indigenous knowledge is “embedded in Indigenous languages, cultures, lands and territories, and laws and ceremonies” and must be implemented, in a culturally-safe way, into social work practice (Greenwood et al., 2017, p. 182).

The UNDRIP (2008) document calls upon settler-colonial policies and practices that disregard Indigenous practices as invalid to be abolished. UNDRIP (2008) states that Indigenous people have the right to exercise their rights, which include having autonomy in individual and community decision making, and maintaining and practicing holistic (mental, emotional, physical, spiritual) health practices, including traditional medicine and ceremony; it also stresses the right to live on their traditional territories and access resources, preventing further dispossession. UNDRIP (2008) identifies the boundaries that Canada and the Canadian government is required to adhere to, including working harmoniously with Indigenous people by recognizing and granting Indigenous sovereignty and rights, and by also dismantling and deconstructing any forms of assimilation or destruction of culture. UNDRIP (2008) further indicates that the State must allow for Indigenous nations to maintain and/or re-develop Indigenous institutions for decision making.

Conclusion

Audre Lorde’s famous essay articulates, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (1984). The tools of settler-colonialism have created a system of social services and social work that has not developed to maintain the wellness of Indigenous communities. The core of anti-oppressive practice is to actively engage in decolonization and advocating for autonomy for Indigenous people and communities, while practicing social work with a culturally-safe and trauma-informed lens. It is through these relationships and practices that social workers can create a new narrative as active co-creators and healers within Indigenous communities, rather than continuing to practice as settler-colonial saviours.

Activities and Assignments

- Personal Research: Understand yourself/family/community history on Turtle Island.

- Did your family immigrate to Turtle Island, and (if so) when and from where?

- What cultures / languages did your ancestors practice / speak? Do you practice / speak these cultures and languages?

- Has colonialism / settler colonialism affected you or your ancestors, and how?

- Community relationships:

- In evaluating the chapter contents, which ways might dominant social work differ from community social work in Indigenous communities?

- CASE STUDY: Imagine you are a new social worker within an Indigenous community. A community Elder visits you at the office and begins to ask you questions about your reason for being in community. How can you respond in an anti-oppressive, culturally- safe, trauma-informed way?

- CASE STUDY: A community member, with whom you have worked with throughout their healing journey and goal of sobriety, “graduates” from their substance-use treatment program. At the ceremony, the community member gifts you with a craft they had made. How do you navigate community protocol and the ethics of the CASW?

Additional Resources

- Linklater, R. (2016). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Langara College.

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1-40.

- Fortier, C., & Wong, E. H. (2018). The settler colonialism of social work and the social work of settler colonialism. Settler Colonial Studies, 9(4), 437-456.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (2008). United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

References

Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2006). Métis History and experienced and Residential Schools in Canada. https://www.ahf.ca/downloads/metiseweb.pdf

Alexander, M. (2020). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness (10th ed.). The New Press.

Arges, S., Abdulahad, R., & Delaney, R. (2010). Deconstructing the southern metaphor: Moving from oppression to empowerment. In R. Delaney and K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern & Rural Social Work Practice: A Canadian Perspective (pp. 18-42). Hignell Book Printing.

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2001, December 2). Bringing them home – Frequently asked questions about the National Inquiry. www.humanrights.gov.au/social_justice/bth_report/about/faqs.html#ques9

Bateman, R. (1996). Talking with the plow: Agricultural policy and Indian farming in the Canadian and U.S. Prairies. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XVI(2), 211-228. http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/16.2/bateman.pdf

Bear, C. (Host). (2008, May 12). American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many. In Morning Edition. NPR. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865?storyId =16516865

Beddoe, L. (2007). Change, complexity, and challenge in social work education in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Australian Social Work, 60(1), 46-55.

Beddoe, L. (2013). ‘A profession of faith’ or a profession: Social work, knowledge and professional capital. New Zealand Sociology 28(2), 44-63.

Bleau, D., & Dhanoa, J. (2021). Behind the front lines: Realities of racism and discrimination for IBPOC social workers [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed flexible learning: Classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. International Journal of Child, Youth & Family Studies, 7(2), pp. 218-239.

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). CASW code of ethics. https://www.casw-acts.ca/files/documents/casw_code_of_ethics.pdf

Chansonneuve, D. (2006). Reclaiming connections: Understanding residential school trauma among Aboriginal people. Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Collier, K. (1984). Social work with rural peoples. New Star Books.

Collier, K. (1993). Social work with rural peoples (2nd ed.) New Star Books.

Collier, K. (2006). Social work with rural peoples (3rd ed.). New Star Books.

Delaney, R. (2009). The philosophical and value base of Canadian social welfare. In F. Turner & J. Turner (Eds.), Canadian social welfare (6th ed., pp. 8-23). Prentice Hall, Allyn and Bacon.

Fortier, C., & Wong, E. H. (2018). The settler colonialism of social work and the social work of settler colonialism. Settler Colonial Studies, 9(4), 437-456.

Gahman, L., & Legault, G. (2017). Disrupting the settler colonial university: Decolonial praxis and place-based education in the Okanagan Valley (British Columbia). Capitalism Nature Socialism, 30(1), 50-69.

Gaudet, C. (2017). Pimatisiwin: Women, wellness and land-based practices for Omushkego youth. In M. A. Robidoux & C. W. Mason (Eds.), A land not forgotten: Indigenous food security & land-based practices in Northern Ontario. University of Manitoba Press.

Giannetta, R. (2021). Canadian justice/Indigenous (in)justice: Examining decolonization and the Canadian criminal justice system. Journal for Social Thought 5(1), 1-11.

Greenwood, M., Lindsay, N., King, J., & Loewen, D. (2017). Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. Alter Native: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(3), 179-189.

Hart, M., Sinclair, R., & Bruyere, G. (2010). Wícihitowin: Aboriginal social work in Canada. Langara College.

Hunt, S. & Craft, A. (2021, February 26). Sovereignty, intimacy, and resistance: Legal and relational responses to gendered violence and settler colonialism [Webinar]. University of Guelph.

Jacobs, M. C. (2012). Assimilation through incarceration: The geographic imposition of Canadian law over Indigenous people [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queen’s University.

Johnson, H. (2020). Peace and good order: The case for Indigenous justice in Canada. CNIB.

Joseph, B. (2018, November 27). Insight about 10 myths about Indigenous peoples. Indigenous Corporate Training.

Kamin, A., & Beatch, R. (1999). A community development approach to mental health services. In R. Delaney, K. Brownlee, & M. Sellick (Eds.), Social work with rural and northern communities (pp. 303-315). Lakehead University Centre for Northern Studies.

Kelm, M. E. (1998). Colonizing bodies: Aboriginal health and healing in British Columbia, 1900-50. UBC Press.

Kestler-D’Amours, J. & O’Toole, M. (2019, December 5). Nations divided: Mapping Canada’s pipeline battle. Pulitzer Centre.

Kurtz, D. L. (2013). Indigenous methodologies: Traversing Indigenous and Western worldviews in research. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 217-229.

Levin, D. (2016, May 24). Dozens of women vanish on Canada’s highway of tears, and most cases are unsolved. The New York Times.

Linklater, R. (2016). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Langara College.

Locke, B. L. & Winship, J. (2005). Social work in rural America: Lessons from the past and trends for the future. In N. Lohmann and R.A. Lohmann (Eds.), Rural social work practice (pp. 1-24). Columbia University Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Sister Outsider: Essay and Speeches (pp. 110-114). Crossing Press.

Lu, L., & Yuen, F. (2012). Journey women: Art therapy in a decolonization framework of practice. Elsevier Journal: The Arts In Psychotherapy, 39, 192-200.

Macy, E. (2020). Don’t bite the hand that feeds you: Environmental and human exploitation sold as prosperity. Tapestries: Interwoven voices of local and global identities, 9(1), Article 4.

Maracle, L. (1996). I am woman: A Native perspective on sociology and feminism. Press Gang Publishers.

Martinez-Brawley, E. (2000). Close to home: Human services and the small community. NASW Press.

McKibben, B. (2016, September 6). A pipeline fight and America’s dark past. The New Yorker.

Morris, C. (2021, April 8). Sharing Mela’hma. [Presentation]. Aboriginal Mental Wellness – Community of Practice, BC, Canada.

Nelson, C.H. (1986). Innovations in northern/rural community-based human service delivery. [Paper presentation]. Learned Societies Conference, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

O’Neill, E. (2006). Holding flames: Women illuminating knowledge of s/Self transformation [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto.

Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction. (1892). In R. H. Pratt (Ed.), The advantages of mingling Indians with whites (260–271). Harvard University Press.

Perry, B. (2006). Fear and learning: Trauma-related factors in the adult education process. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 110, 21-27.

Pratt, R. H. (1892, June 23-29). The advantages of mingling Indians with Whites. In Isabel C. Barrows (Eds.). Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction (pp. 45-59). Geo. H. Ellis Press.

Pugh, R., & Cheers, B. (2010). Rural social work: An international perspective. Policy Press.

Robidoux, M. A., & Mason, C. W. (2017). A land not forgotten: Indigenous food security & land-based practices in Northern Ontario. University of Manitoba Press.

Rodriguez, J. (2021, May 25). Indigenous, rural residents left ‘more isolated’ after Greyhound leaves Canada. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/indigenous-rural-residents-left-more-isolated-after-greyhound-leaves-canada-1.5442354

Schmidt, G. (2010). What is northern social work?. In R. Delaney and K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern & rural social work practice: A Canadian perspective (pp. 1-17). Hignell Book Printing.

Shepherd, R., & McCurry, P. (2018, October 31). Ottawa must talk to Canadians about nation-to-nation agenda. Policy Options.

Sinclair, R. (2004). Aboriginal social work education in Canada: Decolonizing pedagogy for the seventh generation. In First Peoples Child & Family Review, 1(2), 49-61.

Statistics Canada (2018). Rural area (RA). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/92-195-x/2011001/geo/ra-rr/ra-rr-eng.htm

Stiffarm, L. A. (1998). As we see–: Aboriginal pedagogy. University Extension Press.

Thomas, R., & Green, J. (2020). A way of life: Indigenous perspectives on anti-oppressive living. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(1), 91-104.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1-40.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2014). Unbecoming claims. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 811-818.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (2008). United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Walker, C. (2015, May 29). New documents may shed light on residential school deaths. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/new-documents-may-shed-light-on-residential-school-deaths-1.2487015

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Pub.

Wolfe, P. (2007). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387-409.

Yeung, S. (2016). Conceptualizing cultural safety: Definitions and applications of safety in health care for Indigenous mothers in Canada. Journal for Social Thought, 1, 1-13.

Zapf, M. K. (1985). Rural social work and its application to the Canadian north as a practice setting (Vol. 15, Working Papers on Social Welfare in Canada). University of Toronto.

Zapf, M. K. (2010). Northern service delivery: Strategies and considerations. In R. Delaney and K. Brownlee (eds.), Northern & rural social work practice: A Canadian perspective (pp. 1-17). Hignell Book Printing.

In line with a feministic perspective the authors would like to recognize that there is no hierarchy in the contributive efforts of this chapter and acknowledge that this chapter would not have been possible without the differing intersectional perspectives of each author.

Violence against women is still prevalent in Canadian society and directly impacts not only women and their families, but also the collective community. In rural, remote, and northern communities across Canada, pre-existing vulnerabilities and risk of violence against women[1] is increased and often experienced through Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Domestic Violence (DV). The frequency of violence against women is a direct reflection of the ongoing social problems in Canada resulting in the inequality of women (e.g., historical, social, political, cultural, and economic, etc.). Conroy (2021) identifies that in 2019, the rates of family violence in remote and rural Canadian communities was 2.0 times higher than in the rest of Canada, and intimate partner violence was 1.8 times higher in rural and remote communities.

While these statistics are concerning, Gracia (2004) suggests that the majority of IPV and DV against women often goes unreported due to a multiplicity of societal oppression(s), personal circumstances, and barriers to accessing support. However, those who live with multiple intersectional ties may be at a higher risk of violence, particularly Indigenous, immigrant, and Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgender/Intersex (LBTI) women living in rural, remote, and northern regions (Calton et al., 2016; Daoud et al., 2013; Murshid & Bowen, 2018).

This chapter focuses on IPV against women in rural, remote, and northern regions. However, it should be noted that while women may also perpetuate violence, that will not be the focus of this chapter. Furthermore, it provides an opportunity to learn and reflect on the prevalence of IPV and DV in rural, remote, and northern communities within Canada and how social work practitioners support the work being done at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. Social workers providing services in these communities need to be aware of risks, how to provide risk assessment, and how to incorporate safety considerations for those who may be experiencing IPV and DV.

[1] In this chapter the term “woman/women” refers to cisgender, trans, intersex, and anyone identifying as a “woman.”

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the following learning objectives should be achieved:

- Understanding of definitions of IPV and DV and awareness of the rates and the historical context for this issue in Canada, specifically in rural, remote and northern communities

- Awareness of implications for social workers working with victims of IPV and DV in rural, remote, and northern communities across Canada

- Understanding of specific safety planning and practice considerations for social work professionals on a micro, mezzo, and macro level

- Awareness of the importance for social workers to develop collaborative working relationships, and educational and advocacy opportunities to reduce the severity and frequency of IPV and DV occurrences.

Theoretical Framework

The complexity of violence and its impact may be best understood through a feminist, trauma-informed, intersectional lens. In alignment with a feminist perspective, this chapter uses the term “survivor,” rather than “victim,” as the word “victim” pathologizes and disempowers the woman who has experienced violence (Walker, 2002). Feminist theology serves to empower women and raise awareness that disparity and oppression within larger, structural, and political systems exist (Corbeil et al., 1983, as cited in Walker, 2002). In combination with a trauma-informed lens, principles grounding our understanding of domestic violence include the following: safety, trustworthiness and transparency, collaboration and peer support, empowerment, and choice for survivors (Bowen & Murshid, 2016). Applying these principles in understanding violence, in order to support survivors, highlights a useful approach to providing care that is not re-traumatizing. In addition, using an intersectional lens allows individuals to gain a deeper understanding of IPV and DV. For example, Sokoloff and Dupont (2005) explain that violence experienced and reflected among an individual’s social locators (e.g., culture) may be interpreted by the survivor differently than by witnesses or observers. Therefore, it is important to be aware that cultural differences should not mask the larger systemic and structural forms of oppression (e.g. racism, colonialism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, patriarchy, economic exploitation, etc.) that impact and increase violence for women across diverse social locators (Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005).

History of Domestic Violence in Rural, Remote and Northern Communities

Canada is a vast country, with most of its population residing in large urban cities (Moffitt et al., 2020) and an estimated 19% of Canadians in rural and remote areas (Statistics Canada, as cited in Graham et al., 2017). Historically, the violence perpetrated against women has been embedded in many institutions and remains entrenched covertly and overtly in our current systems. For example, the women’s suffrage movement and resistance against the dominant, patriarchal Canadian society began in Manitoba in 1916 (Parliament of Canada, n.d.). Other provinces, such as Saskatchewan and Alberta, followed suit until, on a federal platform, Canada conceded to the pressures of change (Parliament of Canada, n.d.). However, while there were a number of significant changes and rights acknowledged in the 20th century, violence against women continues to be a significant issue (Sitter, 2017). Walker (2002) highlights that during the 1970s, a network of shelters was developed across North America in response to violence against women (Government of Canada, 2021b).

Service Delivery

The delivery of safety services for survivors of IPV continues to be an area of advocacy research/development and ongoing evaluation for social workers in Canada. While DV does not differentiate among geographical locations, social workers working in rural, remote and northern areas of Canada have unique service delivery needs and limitations based on resources and location. The implementation of IPV policies that have been developed and implemented in more densely populated areas of Canada are often inadequate in meeting the needs of rural, remote, and northern communities.

Policy

Policy development for IPV and DV continues to be an area of concern, since several Canadian provinces lack legislation to support the survivors of violence. In 2021, six provinces (Alberta, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan) and three territories had implemented legislation to support survivors of IPV, in addition to the laws set forth in the Canadian Criminal Code (Government of Canada, 2021b). The Criminal Code is meant to prohibit some forms of IPV, including “physical and sexual assault, some forms of emotional/psychological abuse and neglect, and financial abuse” (Government of Canada, 2021a, para. 3); however, further support is required to address intimate partner violence (IPV) across Canada.

As part of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women’s work conducted in 1980, there were key changes and suggestions made and implemented in the Criminal Code to address the issue of IP V at the time (Ad Hoc Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group, 2017). Other examples include an amendment in 1983 to protect partners in their intimate relationships from such acts as spousal rape, and in 1993 to include criminal harassment (i.e., stalking) (Government of Canada, 2021b). More recently,

…in June 2019, the Criminal Code was amended to strengthen the criminal justice’s response to IPV, including by defining ‘intimate partner’ for all Criminal Code purposes and clarifying that the term includes a current or former spouse, common-law partner and dating partner. (Government of Canada, 2021b, para. 5)

With that said, between 1974 and 2001, there was a 62% decrease of spousal homicides, suggesting that many of the changes had the desired effect (Ad Hoc Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group, 2017).