Checkout

Three years after my father died, my mother accepted a two-year contract to teach English in another country halfway across the globe. I felt oddly numb when she left. Recalling that moment now, I realize that Mother’s recurring “cat story” she told years ago was coming true. As the kitten, I was all grown up and beginning to purr without my mother.

But the sound within me was horribly wrong. Deep within, the purring turned into mewling, then flowered into a howling scream.

Mother was out of the country when a ticking emotional time bomb detonated from my solar plexus. The explosion sent me to a psychiatric unit for two weeks. Horn in hand because I had just finished a gig, I arrived at the psychiatric wing of the Miller Dwan Hospital to inquire about getting medicine for minor depression.

Earlier that morning, I had attended my usual AA meeting in Superior. I fought the urge to drive off the high bridge on my way back to Duluth. Crazy, impulsive ideas had been popping up with alarming frequency. A couple days before, I fancied buying a gun so I could blow out my brains.

What stopped me? Fear. Not of dying, but of trashing my reputation as a musician. Other than those pesky suicidal thoughts and plots, I thought I was maintaining my sanity rather well. So long as I stayed on task with scheduled rehearsals and gigs, I could wait out this emotional slump.

Or so I thought. Julie, my first friend made in Duluth and fellow musician, offered a different scenario of this slump.

“Sadie, you have been down for a very long time, and I am worried.”

“Oh, you know me, Julie, I always get it together eventually.”

“Well actually, I am not sure of that. I know who you are any more. I literally don’t recognize you sometimes.”

“What the hell does that mean, Julie?”

“You scare me with how often you talk of chucking it all. I’m afraid of losing you.”

Soon after Julie shared her concerns, an A.A. friend expressed similar concerns. After the meeting, she drew me aside.

“You know, Sadie, we don’t take each others’ inventories in A.A. But I need to tell you that I am hearing some really self-destructive ideas coming out of your mouth.”

“Yeah, yeah, the stinking thinking, I’ll tone it down. Julie told me this too.”

“No, it’s gotten beyond that. You say scary stuff, then smirk as if to blow off as a joke, but it isn’t. I see the slump in your shoulders.”

“Well, as they say, this too shall pass.”

“But sometimes we need help beyond meetings for that. Why don’t you stop by the nurses’ desk at the Miller Dwan sometime and check things out about how you’ve been feeling? Sadie, I’m really worried about you.”

“The psych unit? Weren’t you were a while back? I’m not that bad, not like you were. It’s just some mild depression. I’ve had this before. Good gods, did you and Julie call each other up and plot to push me around?”

“No, Sadie, we did not talk, but we are your friends. Please, get someone who’s a pro to confirm it, and to maybe suggest a medication or some sessions with a counselor. It wouldn’t hurt to have a medical perspective.”

“Well okay, I promise to go. Right after I finish playing a wedding gig.”

Sorely wanting to drive off the bridge again as I drove across it after the meeting, I envisioned relief at plunging my car into the bay. I longed to sink into oblivion, stop the noise inside and the nagging about how I was being a downer. But I couldn’t bear the thought of disappointing my friends on their wedding day. I had promised to be there and play for their nuptials.

The day before, I had mused at length over the feasibility of blowing my brains out. But an orchestra rehearsal that day interrupted my line of thinking then. What is wrong with me, I mumbled aloud.

My mind seemed lately on a racing track, speeding through various strategies for leaving the planet. But just as soon as I had an idea, I also thought of their impossibilities. Part of me persisted in churning out self-destructive thoughts, while another part pointed out the impracticality of following through.

Like the gun. There wasn’t enough time to shop for a handgun, get drunk enough to muster up the courage to use it, and still make rehearsal. That plan was foolish anyway because I didn’t want to ruin my sobriety date – and I would have to be drunk to muster up the courage to pull the trigger. And then following Dad’s footsteps, and Uncle Roy’s with the gun thing. No. And I would lose my symphony job if I were drinking again. Then Gregg and Julie wouldn’t be our friends anymore. There, matter settled. Not going to kill myself today.

It seemed my mind never ceased seeking a way out, the thoughts increasing daily, interrupting. What if it made me miss a note? Then my reputation as a good musician would be compromised. I told myself “Focus, Sadie, you have a gig. Then you need to go home and make supper, and practice for orchestra rehearsals coming up.”

Inpatient

I made it across the bridge and got to the wedding, and played just fine. On my way home, I remembered my promise to my A.A. friend and decided to stop by the nurses’ desk on the second floor of the Miller Dwan Health Center. Just a quick chat. I didn’t think the parking lot looked safe, and so I brought my horn in with me and buzzed the bell for the psych unit. I planned to explain my need for an antidepressant, get a prescription filled downstairs, and go home.

A staff member opened the door, smiled, and invited me in. I told them, “I’m here to ask a few questions about depression.” The staff member led me to a quiet, comfortable room with a small table and windows showing a stunning view of Lake Superior. I waited there for a few minutes before a nurse came in to get some basic information.

Soon I was chatting with the nurse about my need for an antidepressant, with contingencies. I explained that I was a very busy musician who needed to get home soon to make supper and practice afterward. Why I disclosed all of those pesky suicide thought to the nurse at the intake station of the psych ward was beyond me; I smiled and assured them I would be just fine if I got some antidepressants.

The nurse coaxed me into relinquishing my horn to a storage room, ostensibly for safety reasons (the crazy patients might damage it). She asked me to stay there while she found a counselor who needed to ask me a few more questions. A kindly man entered with a clipboard and an ID badge that had all sorts of letters after his name. He asked me about the kind of depression I was experiencing.

Although the counselor seemed pleasant enough, I found myself struggling to answer even the simplest questions about my job and my husband. The pervasive exhaustion I had been ignoring, resisting for months, suddenly emerged and engulfed me, relinquishing control over my efforts to mask how awful I really felt.

Out of my mouth blurted an odd query to the counselor.

“Are we safe in here?”

“Safe? What do you mean?”

“Do the doors to the psychiatric unit keep out bad people?”

“Indeed, we are all safe. Especially you, Sadie. Tell me what’s going on.” The counselor held my gaze.

“Well, okay. I might have been feeling more than little bit depressed lately.”

“Let me assure you, Sadie, that you are completely safe here. And so that means you can tell me if any of your symptoms are related to your husband’s behavior.”

“Dave? Oh gosh, no, no not at all. Dave is amazing, he is the best. I don’t know why he sticks around, actually, I’m such a mess. He has a really tough time putting up with me. I mean, if I were gone, he’d be a lot better off without me.”

The intake counselor wrote a couple words on his form, then looked up again at me with a sincere expression of warm encouragement to continue.

“I’m so glad you have a good partner. What about family, then, are they close by?”

“Umm…no, they…ahhhh…”

Growling, howling, noises moved into my temples. Deep, penetrating exhaustion soaked through my clothing and into my bones. The counselor’s voice felt far off as he continued asking me questions.

“Are your parents still alive?”

“How did your father die?”

“How long is your mother going to be abroad?”

“How is your overall relationship with your family?”

Dizzy, I couldn’t connect to my own voice answering. I couldn’t shut it up. I shook my head NO.

“Why don’t you want to talk about your family, Sadie?”

BOOM. The question jettisoned me into a different realm. I felt small, vulnerable, terrified. The growling intensified, breaking loose and filling the room. Stunned at my lack of self-control, I trembled like a fearful child at his questions about my family of origin. No, I didn’t want to explain or talk about it. Yes, I was afraid, but I didn’t want to tell why.

Incomplete sentences spilled out of my mouth, then uncontrolled gibberish. So much for that fancy graduate degree, I looked like an idiot. Gads, would I also pee my pants too and be a complete loser?

Shouting inside the painfully discordant howling and buzzing in my head I heard threats: “

Shut up!

Liar, you ungrateful brat, everything is fine, your childhood was great

Don’t you dare say another word or I’ll kill you!

Weeping, I wailed that I must die rather than talk. Then I abruptly shut up and shut down, mute as a granite boulder. My behavior led the interviewing counselor to admit me to the locked psychiatric unit. I had failed the test. The admitting nurse called Dave, who arrived while the staff was moving me to a private room that had thick bars over its lone window.

Bars on the Windows

While I was exchanging my shoes for paper slippers and changing into hospital-ugly clothes, a team of counselors led Dave to a consulting room. They grilled him with questions to determine whether he was abusing me. Then they softened their approach and asked him to describe my moods and behavior. He had been deeply worried about me for months, afraid that I was slipping away from him.

Finally, Dave and I met in the common room of the psychiatric locked ward, permitted to talk quietly while my intake papers were completed. Holding hands, we watched the other patients mill about. Some were talking to themselves, to the walls, or to their stuffed animals. Horrified, with tears in his eyes, Dave promised that he wouldn’t let me go crazy like them. I replied that I might already be crazy, but I didn’t want to be locked up with these nut cases.

Visiting hours ended. Dave led me back to my room and held me close in a big bear hug until it was time for him to leave. I told him I would work really hard on figuring out how not to kill myself. He left the psych unit in tears.

From my window, I watched as my beloved soulmate shuffled toward his car in the hospital parking lot. It was nighttime now and rain had moved in from the clouds hovering over Lake Superior. In the middle of the parking lot he paused, turned, and looked up at the second floor of the building, searching for me. He found me peeking through the bars, crying. For a long while we held each other’s gaze, our tears merged with the rainy drizzle.

What was wrong with me, I despaired as I watched Dave’s car go out of view. I had a master’s degree and a budding career in music. We loved each other. We had friends, colleagues. I had seven years of quality sobriety. I believed in God. My life was the best it had ever been. Deep down, I knew I deserved none of it.

Noxious, buzzing howls at the periphery of my mind condemned my utter worthlessness, my un-lovability. Underneath it all, a low throbbing hum assured me that I was fundamentally no good, lazy, phony. It would be a great favor to Dave and the world if I exited the world as soon as possible.

Yes, I thought as I wept lying face down on the plastic mattress in my room, the doctors will agree that I’ve lost my mind and sanity. They would uncover all the damning evidence of my psychotic inner world. They would expose the nightmares plaguing my sleep and torture the child in them for continuing to bellyache about nothing. They would see the snippets of terrible scenarios running through my brain and conclude I was the biggest liar ever.

All that I had long banished into the “big lies” quadrant of my mind were now surging forward into my consciousness to expose me as “nucking futs.” I hadn’t a clue what was real. Curling up on my plastic mattress in my grubby yellow scrubs and booties, I predicted an eminent end to my sober, grown-up life.

A nurse came in and offered to sing to me to soothe me.

“Would you like a lullaby, Sadie?”

“Are you making fun of me?”

“No, I’m asking if my singing would calm you.”

“Yeah, right, just rub it in that the music has died. Do you get paid extra to taunt the new inmates?”

The nurse left abruptly, marking a couple boxes on her clipboard as she secured the door open.

“We’ll be needing to watch you tonight, Sadie, so no closed doors.”

“What did you do with my horn? Did you throw it in the trash?”

After three days in the locked unit, the hospital staff moved me to the other side of the psychiatric ward. There were no bars on these windows. My scrubs were now a light blue, but shoes were still off limits (laces can be crafted into a noose). My horn, I was told, was safely stored somewhere.

To my surprise, my team of psychiatrists and therapists concluded that I was far from crazy. They diagnosed me as has having severe, chronic suicidal depression from Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD).

This condition, explained to Dave and me during a family consultation meeting, stemmed from “un-grieved losses yet to be identified and articulated fully by patient.” Neither of us understood what this that meant, but I willingly accepted meds for it. I also signed, reluctantly, an agreement to a two-week stay at the hospital.

The Padded Room

Hoping to boost my mood, the nurses gave me back my horn to practice when I wasn’t in a therapy or activities session. I laughed when they offered the only room suitable for practice – the Padded Room (yes it exists in psych units!) – to avoid disturbing other patients. Each time I was escorted over to the locked ward to play my horn, I wondered whether it was a trick to lock me up forever. But the padding dampened my sound enough to avoid interrupting the psychiatric ward’s daily work.

I came to appreciate the feeling of being safe with my horn, closed off from the world. During those “padded room practice sessions,” it became profoundly clear how music had been a constant life force my entire life. In a counseling session during my stay, I wondered if my very soul had been born out of music, somehow ordained by a Divine energy before I was even born.

Whatever doubts I had before about whether music was my true vocation, they all evaporated in the illuminating (yet padded) light of my hospitalization. I reasoned that they too resonated with the authentic pitch of my core identity. Music would help me find my way back to a life worth living. Returning to my chair in the symphony horn section, though, I could not yet see how.

On the horizon of my thirtieth birthday, I sensed tectonic plates shifting within. An ugly emotional lava began to spew over the inner emotional walls that therapy had been deconstructing. Those walls had been protecting a frozen vault of something yet unnamed. I feared that my cherished marriage or career – or both – would be torn asunder by a lurking terribleness.

On a chilly day in May, Dave and I relaxed on the Park Point beach and beheld the expanse of Lake Superior. We watched April, our new black lab puppy romp in the sand and water. There weren’t any trees to sing with me, but I smiled at the wind as it whispered a lovely tune. Underneath it, I heard another sound beckon. Within the wind now came a voice that seemed a cousin to the trees.

Rushing in on the waves, the winded messenger whispered an urgent message: “It’s time to wake up.”

To this day, I can bring forth that moment when I heard that powerful message. Over the next two years to come, waves of memories more powerful than Lake Superior’s waters crashed into me. They commanded me toward admitting, finally, what my mother had done.

Waves of Truth

Processing memories feels like the vomiting stage during a bad bout of the flu: ceaseless throwing up, with dry heaves, fitful sleep is fitful between purges. Twenty years of retching up all over my life what I had stuffed seemed to take forever to clear out. Feelings seemed to rage through me like a virus with multiple symptoms.

Freeze-dried in an emotionally cryogenic chamber, I had kept my feelings under strict control as unresponsive, disembodied dead things. Now some idiot had switched off the temperature control and I was sweating with feverish pains from a past I had disavowed.

I railed against my new powerlessness to stop the flood of flashbacks and nightmares.

Desperate to stop the memories from playing out, I burned and cut my skin, alternately trying to numb the truth or punish myself for lying. It simply added to the chaos. I felt so helpless from the glut of feelings that at times I became disoriented from my bearings of the present time. Surely, this time I really was losing my mind! I wanted to return to the psychiatric unit and live there.

Everyone assured me that feelings never killed anyone. Dave, though, feared he would come home from work to find me dead. He arranged for friends to drop by and spend time with me. Julie later told me how all worried what they would find when they arrived. Would they find me playing with Legos, painting, practicing my horn, or writing out lesson plans? Or would they have to pull me out from hiding terrified in one of the closets with a stuffed animal, asking them to make sure Mother was not looking for me?

Comfortable Settings and Songs

My attention span waned again, but not because of rehab from drugs or alcohol. My brain was overloaded with memories and feelings that no longer stayed in place where I had banished them in my mind. In balance with my favorite orchestral tunes I began listening more often to popular tunes. James Taylor especially appealed to my ears for his gentle, melancholy crooning.

Taylor’s tune “Secret ‘o Life” waxes philosophical, coaching his listeners to embrace the passage of time as an almost spiritual pathway to healing. A verse that begins “Now, the thing about time is that time isn’t really real/It’s all in your point of view/How does it feel to you?” encouraged my work to merge past and present realities. The lyrics also acknowledge that “It’s okay to feel afraid/but don’t let that stand in your way.” To me, this seemed a much gentler way to approach the way ahead than my mother’s credo to ignore all fear and do it anyway.

Cyndi Lauper’s music never ranked very high in my list of pop favorites. However, her anthem “Time After Time” aptly described my experience of feeling tremendously loving support from people who truly cared about me.

An army of allies, Dave leading the platoon, spent years building me back up from flashback episodes. Their approach was simple and intuitively powerful: They loved me unconditionally. They reminded me, countless times, that I was safe, strong, well, and whole. They grounded me into their experience of the person they knew by including me in their lives, and by re-engaging me with the life I had created as an adult.

This remarkable crew of allies included musicians, fellow recovering alcoholics, other incest survivors, teachers, and spiritual believers, all pouring out love from their immeasurably huge hearts to nurture me. In the center stood Dave, doing his best to navigate it all. His family was there too, accepting me even if they didn’t understand what all was going on. Kathi and Joe embraced us, included us, and loved us whenever we found our way to their home for renewal.

Especially tender was Dave’s mom, who had read an essay in a magazine about someone who’d been abused as a child. She wept at the story’s unsparing descriptions, asking Dave afterwards “Oh my God, is this the level of abuse that Sadie went through too?” At our next visit to the family, she held me tightly with tears in her eyes. She announced “I’m your mom now. I love you, and I won’t hurt you. I’m here.” She stepped into the maternal role from then on, and I’m better for it. Likewise, Kathi has been the sister I always needed and deserved.

That my allies felt certain of my resilience to get through this projected a vision beyond survival. Frankly, I doubted them for a long time. Reminding me that I already had done so as a child, they insisted I could survive now. Further, they believed that I would one day thrive. I needed an entire crew like this to lead me back (sometimes literally) to the present the reality of my rich, rewarding life with Dave.

It was excruciating to tell others what happened. Denise from Pittsburgh listened patiently at the other end of the phone line, taking it all in. Her belief in me never wavered. Julie cried buckets of tears with me, many many times, and made sure that I ate (and had coffee!). Jane and Kurt came over and helped me through bad days. I let in a couple musicians like Mina, who graciously helped me stay on track at concerts.

Musician’s Focus

The skills of professionalism I had developed in sobriety provided an essential structure for moving through adversity. This time, I had to move through the processing of memories. I applied these skills to re-engage with my current life. I knew how to practice my horn parts, and I capably collaborated with fellow musicians in rehearsals and performances. I knew how to teach horn lessons, and my knack for teaching lecture courses drew upon my true desire to engage students with the learning process. Still though, my confidence sagged with a self-deprecating mindset that I was an imposter. I replayed all sorts of regrets about my past.

Showing up to work required tremendous energy – and the self-discipline of a professional musician – to compartmentalize all of that mess in order to bring a calm, attentive demeanor to completing tasks at hand. My position as third hornist of the local professional symphony often bridged me back to the present.

On days when I’d had flashbacks it was a mighty struggle to suit up and show up to play horn. One evening before an orchestra performance, I knew that I was trapped in some sort of schism between past and present. I couldn’t recall why I was wearing all black and sitting onstage, and I asked Dave what the hell I was doing there. With a knowing look to the fourth hornist, Dave put my horn in my hands and said, “you know how to do this.” As he took his place at the timpani, he held my gaze.

Through the entire first half of the concert, my colleague on fourth horn prompted me to play by pointing to my place in the music and counting off a couple measures before my entrance. As soon as the horn was on my face, I did indeed know what to do. Then I would again slump in my chair during passages of rest, rousing only at another prompt of her counting and pointing. By the end of the concert I had merged back into myself fully.

Memories of my childhood, now given room to rise and breathe during Mother’s extended absence out of the country, came out from behind other sounds that had masked them. Uninterrupted by phone calls or visits or regular letters from her, all that had been lashed down inside me now freely unraveled without fear of retribution. No one in Minnesota had a vested interest in shutting me down.

So long as Mother remained far away, my inner world could come forth and howl various dissonant grievances of what had happened. The howling demanded my attention, demanded the reality I had withheld from them for years.

To live fully the whole life I desired, I had to embrace the totality of myself. No longer could I selectively check out of unwanted thoughts, feelings, memories. Integrating all that I had pushed away in order to survive sent me into the very sounds I had been avoiding in my inner world. There was no more balancing between inner and outer; it all had to come together. Just when I thought I had managed this, another wave of frozen feelings would crash into me and throw me over the retaining wall separating the two realities of my being.

Music seemed to shift keys, modulating inside and out, wandering around as though it were looking for the right chords to end a thought. Inside, I heard jumbles of sounds that interrupted my thoughts suddenly. I couldn’t quite catch my breath, and I questioned every step toward the jumbling mess of sound. How could any music survive in that morass of horrible noise?

The positive interventions of friendship, education, sobriety, and especially Dave and his family built up my reserves of strength to walk through it. They shored up my sense of self and also reminded me of all that I had to build my own self-confidence. I was sober, gainfully employed, and socially functional on days when I wasn’t swirling in memories. Through it all was a fiercely powerful unconditional love from Dave, and the rewarding life we were building together in Minnesota as professional musicians.

When Dave and I began dating, I happily availed myself of his record library of jazz artists. Dave loved the music of jazz pianist Bill Evans, and I immediately loved it too. I lack the vocabulary to describe Evans’ signature musical language, but it speaks to me on similarly deep levels of contemplation and melancholy. Like many of his contemporaries, his brilliant artistry seemed ever at odds with his addiction to heroin and other substances. I knew nothing of Evan’s life when I began listening to his music; I just connected with it.

Dave framed the lyrics to one of our favorite Bill Evans tunes: a setting of “You Must Believe in Spring.” Michel Legrand wrote the tune but Evans made it poignantly relevant to our lives. Rather than attempt to describe it here, I suggest readers experience it for themselves. I’ll just post the ending phrase: “you must believe in spring and love.”

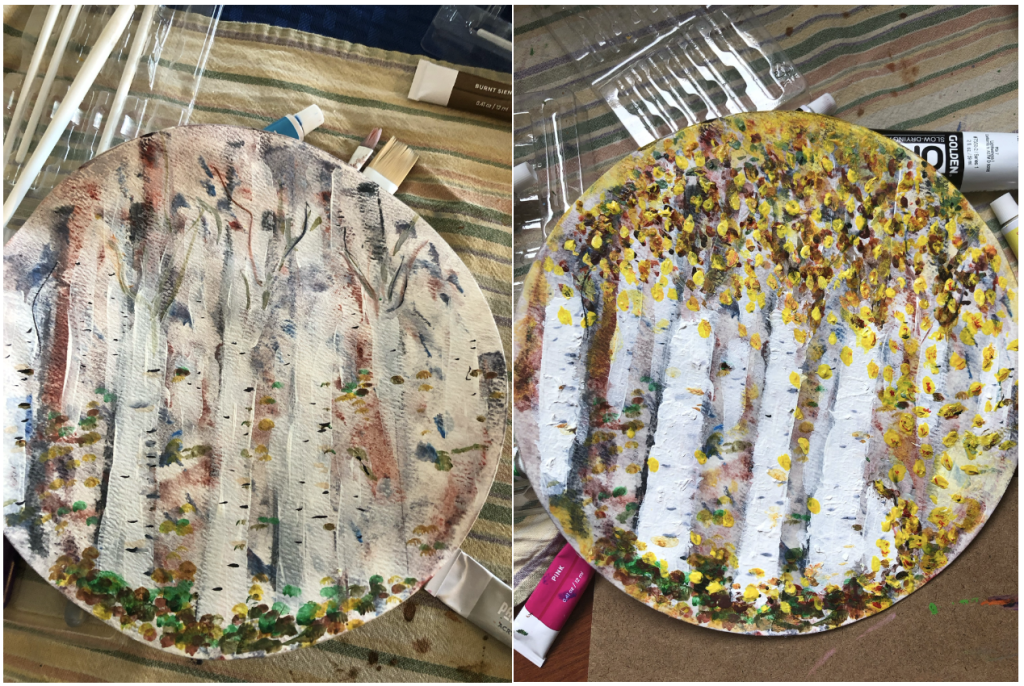

Much as I understood the song’s meaning about rebirth and spring, much of my hurting soul felt like the season of autumn when leaves die. Fall remains my favorite time of year; perhaps some melancholy still lingers in the fringes of my being.