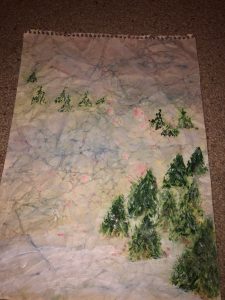

God’s Forest

Frozen in a recessed vault of unprocessed memory, I locked away the truth of what happened to me for many, many years. My mind went about its vigilant task of constructing a pain-free conscious reality, as though the vault didn’t exist at all. Unfreezing my silence decades later wrought painful reverberations more excruciating than recovering from frostbite.

My survival depended upon linking my musical sense of being to the nurturing soundscape of the forest, actual musical compositions, and a divine force that I knew as God. In my child’s mind, I determined that I could hear God through music, and that I could be with God in the woods. The “sound of music” to me was no fanciful music drama, but a sincere communion with a Divine Creator, who, I believed, tended to the well-being of unloved children. I had music, and I also had the forest. God gave them both me so that I could wait out the storms of my childhood.

Running away to the woods on the land where I grew up became a sacred, lifesaving practice. I needed someplace to hide, a place where I could create a safe sonic world of my own design. Solitude in the woods provided vital time for me to regain mental and emotional equilibrium.

Weekend in the Wisconsin Woods

After my mother died, a friend invited me to spend the weekend at a woodland retreat in Wisconsin. Each of us had our own cabin. Mine had a big picture window overlooking the woods, and the scene triggered an overlap of time and place. I was at once returned to the woods of my childhood, recalling a similar valley that lay beyond the first bend in my favorite path. The ridge of that path lay just out of sight of the bend, sloping into a secluded valley thick with a snarl of scrawny trees vying for sunlight.

My cabin window vista reminded me of the fallen trees bent low from the winter snow, arcs perfect for swinging or balancing like a gymnastics beam. I remembered how tufts of dead long grass poked through the deep snow. How I had loved those woods.

I fancied that if I stared out my cabin window long enough, my child self would appear on the ridge of the valley beneath the window. I imagined watching her search for sanctuary in the wild as she bushwhacked through the thicket of trees, burrowing into leaves – or since it is winter, into snow like a sled dog cozying in for the night – and crawling into the safety of the earth’s wooded silence. I could watch as she became submerged within herself, far away from what had happened, burying the pain.

Over fifty years later and several states away from my childhood home, I felt keenly attuned to the kindred sounds between the two times and places of my life. Like the jubilant realization of grace in Dickens’s Christmas Carol, “It’s all still here!” I recognized at last how my forest sojourns metabolized trauma into sustenance, enabling me to carry on. Time in the woods facilitated a fusion of energies, conjured up in the imagination of a wounded little girl who wanted to escape an unspeakable ugliness.

From my father, I got the notion that God lived in our forest. Perhaps I merely wished it to be so, for I don’t recall any direct theological instruction from him. A rather private man, he pontificated only on matters legal and political. After a long day in court – whether from the bench or from the other side, where he spent much of his career as a defense attorney – he craved Nature’s solitude. Permission to accompany him fishing or walking through the woods required quiet reverence; I learned to listen to the language of the trees, the waters, and the deer.

Where God Watches Over

A few years before I was born, my parents purchased around two hundred acres of land, and milled lumber from the trees on the property to build a house. The wooded acreage included a large stand of pines surrounding a five-acre pond, and later, a ten-acre pond. Farmers rented some areas of our land to grow their corn, but the place was never a working farm. They intended to create an idyllic country home for a growing family. We kept a vegetable garden, fished for bluegill and bass, and for a short time hunted small game in the woods.

Initially, the idea of hunting on his land appealed to my father; but living among all the land’s creatures gradually transformed his perspective. He continued to fish but became fiercely protective of the animals from poachers who trespassed to hunt “our” deer.

The deer’s vulnerability to human predators resonated with my own sense of being trapped, caught unawares, overpowered. Nowadays the deer population is out of control, but when I was growing up only a small herd of deer lived in our woods. During winter we placed salt and apple licks at the edge of the meadow clearings. Waiting for them to venture out at dawn and dusk became a favorite pastime.

Our ranch style house had a long front patio with breathtaking views – meadows and ponds, neighboring farmlands, the covered bridge over the one-lane tar road. We had to sit very still on the porch so as to avoid startling the deer. Dad took pains to draw upon his cigarette slowly when the deer grazed in the meadow. Under our watchful regard, I grasped that we were mere stewards of land that belonged to them.

Stewardship required all hands in the family for property upkeep. It seemed as though someone was always mowing something – the expansive meadow, the front and side lawns, the banks of the pond or lake, or the paths through the woods. Dad was constantly tinkering with various mowers and the big tractor, keeping us on schedule with the mowing tasks.

I wonder whether my father ever suspected that I purposely mowed over some newly-planted pine trees to be banished from using the big tractor to mow. Really, what I wished for was to mow the paths in the woods. Only Dad had that privilege of steering the rumbling old Gravely toward the trees to clear the walking paths.

My efforts at practiced reverence for the forest were rewarded when I walked with my father after he had mowed through the woods, ostensibly to inspect his work. Emulating his quiet manner, I proceeded thoughtfully with senses attuned to my surroundings, drawing all of it inside of me like a big hug. The fresh pathways beckoned my return on my own to check my favorite stopping places. Mother Nature unconditionally accepted me, offering constant and consistent sanctuary to simply be.

I created many hiding spots and exit routes along the pathways through the woods, often play-acting with imagined bandits or pretend friends. I veered off the paths with abandon and a keen sense of direction. I never got lost.

Scattered throughout the woods of my family’s land, this once battered child bled out onto the ground her broken soul, that she might release all of her anguish into the land in order to survive. To then gather from it all available resources – the soil, the air, the animals, the sun, the sounds of life as it should be – all the sustenance needed to continue on as though nothing had happened, that was a secret and precious grace.

Many an afternoon passed hidden deep in the woods, sleeping beneath leaves or pine needles, playing in areas where no one thought to look for me. I don’t recall my mother venturing into the woods, nor do I recall spending time there with either of my sisters. If Lee ever suspected I was hiding, he left me to my solitude in tacit understanding of our respective woodland sojourns.

It never occurred to me at the time that I led a lonely life, because I shared my experiences and feelings with no one. My confidante and intercessor was Nature, who didn’t need words. Her trees offered arms to sway me in into calm, her waters cried the tears I couldn’t shed, her animals chattered away in companionable understanding.

What few school chums I had rarely visited, and I didn’t invite them into my woods. Anyway, they preferred to go swimming, bang on the pianos in the music room, play indoors, or play with Finch instead of me.

Certainly, the notion that God lived in the woods reflects a normative childlike tendency to make literal meanings out of metaphors. However, a profound experience at age twelve vindicated my conviction, and clarified my desire to seek a transcendent plane of spirituality. This experience, along with two others that occurred in adulthood, shaped my understanding of spiritual mystery.

Close Encounters of the Helping Kind

My cousin Margaret recently reminded me of Biblical instances when God encountered people on the road, in the desert, or in some other starkly stunning manner. It is, she pointed out, altogether common for God to find us in our alone-ness. Inwardly, I wandered along a desert of solitude, but outwardly I traversed a long, winding gravel driveway that led from the road to our house. I walked it nearly every day from third through tenth grade, to ride the school bus.

The long driveway’s walk became complicated when I began playing horn in junior high. The flared bell of the case bumped against my knee, making my gait especially awkward if I had books to carry. My steps were slow, and I focused on balancing each step, noticing little else. Any sudden moves or distractions could cause me to drop books or horn.

The last turn in the driveway marked a resting point before a straight walk up the hill beside the front meadow. I adjusted my cumbersome load and stepped off the gravel into the meadow. Suddenly I saw the neighbor’s dogs trotting out of the woods toward our house. Six German shepherds, sniffing around the chimney and windows, moved like a pack around the house and into the yard.

These were trained attack dogs who had eviscerated the neighbor girl’s beagle puppy and, more recently, pulverized the leg of the neighbor’s relative. They had attacked two of our dogs, killing one of them. They were not supposed to roam free like this.One of the dogs detected me in its sight lines, and herd mentality kicked in.

Barking ferociously, all six of them bounded across the meadow toward me. The phrase “blood-curdling scream” is no mere cliché here, it came up out of my terrified lungs. Then I froze. So did the dogs.

Into that moment of silence came a presence upon me. An energy that hummed with a most brilliant and distinctive frequency, it seemed deeply wise. It communicated clearly with neither audible sound nor the expanse of linear time needed to complete sentences. Calmly, the presence instructed me:

Tell them to go home.

My mouth opened, but no sound came. Suddenly, the energy of the presence exploded from within me.

Go Home! emanated from my chest, in a masculine voice wholly distinct from mine.

GO HOME! The voice boomed across the entire meadow, thundering the command.

Still frozen to my spot in the meadow, I watched the dogs turn back toward the woods. I opened my mouth again. “Go Home!” now rose up normally from my throat. The six dogs ran and soon disappeared into the forest. My arms and legs tightened as I screamed the command from top of my twelve-year-old girl lungs, running toward the woods to make certain they were gone.

Adrenaline coursing through my body, I shook all the way up to the house. My knees buckled at the doorway, and as I collapsed atop my bulky horn, inwardly giving thanks to God. Wait until my dad heard about this!

Excited to share my miracle, I ran into the house and found my sisters, Tressie and Finch. They seemed annoyed that I had interrupted their TV viewing, but I persisted with my story. They rolled their eyes, then snickered dismissively my story as an impossibility. I persisted, but they scolded me for telling lies. Here was yet another example, they sneered, of my active imagination stirring up fantasies. I sunk into familiar feelings of being the family pest and a brat who was too young to know anything.

When my father came home that night, I reported only that the neighbor’s dogs had trespassed. I censored my story about the Voice Of God coming out of the woods to save my life, because I could not bear it if he rejected me too. I vowed that I would believe it, if only just for myself. The deer, the woods, and God would remain my secret allies.

Colliding Sounds of Place and Time

Even now, if I listen deeply and reverently to the stillness of the woods in any place, I can yet remember the lilting songs of a little girl swaying with her trees. Years and miles later, my weekend retreat in Wisconsin re-connected me to the forest memories of my childhood. The walked through the woods offered a joyous reunion with the gracious, healing peace of the wilderness. I returned home from my retreat with newfound awareness – and appreciation – of my resilient self.

Even in new spaces of woodland respite, my mother’s presence lurks at the fringes. It was she who directed me to make a more concrete connection between music and nature, through a recording of “The Moldau” from Ma Vlast by Biedrich Smetena. It was a gift for me, purchased at the local grocery with her weekly household allowance. She loved teaching, and the recording presented an exciting new lesson. Mother was a master teacher; her heart sang through the sharing of knowledge. Where she lacked musical skill herself (she could not match pitch, nor could she tap a steady pulse), she possessed keen intuition for creating “cultural education” projects for her four children and her school students.

Mother routinely plundered her grocery allowance to purchase vinyl recordings for us. The recordings spanned across the repertoire of the western European concert music. I suspect she also squirreled away money to buy us instruments for school band.

Among the records Mother purchased, the most captivating to me was “Vltava,” more commonly known in English as “The Moldau,” a movement from a larger work Ma Vlast (trans. My Fatherland) by Czech composer Bedřich Smetena. It is a musical narrative of scenes along the river Moldau. Calling me into the music room, she piqued my interest immediately.

“Sadie, I bought a new record for you, a story without words.”

“You mean like Peter and the Wolf?”

“No, honey, that has a narrator. This is an orchestra that can tell us about a river far far away, just using instruments.”

“Are they using clarinet like what Finch and Lee play? Or a piano?

“Not a piano, but a clarinet and an entire orchestra. Remember I took you and the other kids to a concert of a big orchestra in the city? That’s what is playing this piece about a river far, far away.”

“Are there pictures?”

“Well that’s what’s so fun. The music makes you think of pictures. This music makes you feel like you are on a boat going down the river, seeing people along the shore; then a big storm comes up and everyone on the boat is scared, but then it calms down. You’ll see, just sit and listen, I’ll explain it to you the first time.”

I could scarcely believe this miracle of creation my mother described as she placed the vinyl disc on the turntable. Someone had figured out how to make sounds in the outside world that painted pictures! I would be able to both see and hear!

What’s more, my mother explained, the music of this far away river in Bohemia had its origins in small tributaries, just like our own little Derby Creek. My daily walks through our forest often included stops to splash in streams leading into this creek, and I played in its waters under the covered bridge down the road. A clever geography lesson on how streams flowed into creeks and rivers emerged, brilliantly clear to me, through the music.

The lilting flute melody at the beginning of the tune sounded like the waters of the stream. My mother expertly narrated the entrance of the other instruments as moving the water from stream to creek to river. She wove a story about how the creek down our road flowed into the Ohio River, ultimately spilling into the great Mississippi. Her story conjured a watery path similar to the Moldau’s story far away. I willed myself to leave the music room and fly along with the musical pictures. My inner landscape of sound grew beyond our forest, beyond our county with its creeks and covered bridges, and halfway across the globe to a mystical place that mirrored my geographical existence.

As a teacher myself now, I play “Vltava” for my students and share with them the memory of my mother softly describing the picturesque scenes of the river as we listened together. The work remains a beloved and popular example of orchestral music designed specifically to suggest non-musical ideas such as nature or rustic scenarios. My students easily grasp the concept of musical representation, and I wonder whether they might one day share this music with their own children.

I gained powerful insight about Ma Vlast during my weekend retreat in Wisconsin: My mother had shown me a way out of pain with that music. A confluence of forces – Mom, Forest, God, Music – instilled within me a sense of existing in time and space through multiple, kaleidoscopic modes. Whether of perception or behavior, these modes could contradict each other, yet coexist in my transcendent space of music.

That my mother both hurt and nurtured her own child suggested that she, too, existed in contrary motion. I could not, therefore, cast her in a simplistic duality of either wholly good nor bad. But my child brain at the time had no capacity for nuanced thought about these complexities of personality. Intuitively, I cleaved to the mother who fed my creativity.

My mother’s creativity seemed limitless whenever she set her mind to that mode. We shared a unique bond of needing to create, feverishly and desperately, against shadows we dared not name. Both of us feared conjuring our shadows into realities we could not bear in a fully conscious state.

Within the teacher showing me a way out by connecting music to nature was also a perpetrator inflicting harm that initiated my desire to escape. Little did I know at the time, that when I violated our code of silence many years later, I would unearth my mother’s own entrenched survival mechanisms. Only then did I realize that the escape routes she had shared with me through her multiple lesson plans in creativity were, in fact, paths she had herself traveled many times.

I could neither save nor heal her.

EXTRA: For a short supplemental anecdote with musical excerpts related to this chapter, click this link: Creeks and Rivers