Of Sound(ing) Mind

Education once again accompanied me along recovery’s routes. I had stopped running from my past, and I had acquired sufficient competency as a professional musician to consider new topics of study in graduate school. I was an experienced teacher and performer. I was studying Russian, and Dave and I had taken our first trip to Russia.

The prospect of another degree in music pedagogy bored me. My continuing struggles with performance anxiety steered me away from pursing a performance degree. When Dave auditioned for a unique doctoral program in percussion that focused on global/world music, I decided on a whim to apply to the music history degree program.

Olga Chaikina, my friend in Petrozavodsk, encouraged me to continue my Russian studies as part of the next step in my formal education. Surely there would be a place for Russia to figure into music history, she reasoned.

I had fallen in love with music history from my brief stint teaching it at UW-Superior. Now I was eager to connect it to my newfound fascination with studying Russian music. Dave and I were both accepted at West Virginia University (WVU), for the coming 1994 academic year. He pursued his DMA in World Music/Percussion, and I pursued a second master’s degree in Music History.

Within a week of our move to Morgantown, I had scheduled AA meetings and interview appointments with therapists specializing in treating complex PTSD. We both received teaching fellowships that offset some tuition enough to minimize loans. This third time around in school, I felt both capable and prepared, finally able to absorb all that a college experience offered.

Planning to continue my Russian studies, I enrolled in second-level language studies at WVU. There I met a creative and intellectual powerhouse in Susan, who also found the back of the classroom the safest place to be. She and I became fast friends in a mutual fascination with the absurd. Susan and I were roomies on a five-week language intensive camp in Petrozovodsk, where we wreaked havoc in many delightful ways.

Cataclysms

A tremendously positive catalyst appeared at precisely the right time, in the form of a lanky, formidable professor of musicology named Christopher Wilkinson. He announced, in the middle of my first semester at WVU, “You need a mentor. I’m it.” I was assigned to teach his Friday recitations of the ubiquitous college “music appreciation” course. He was also my advisor for my degree and the pivotal mentor in steering my path toward musicology.

I agreed to his request of taking a hiatus from performing for at least a year, so that I could immerse myself in learning methodologies of archival research and historiography. Listening beyond Dr. Wilkinson’s gruff façade, I heard that he had traversed alternate routes in his own life journey, most recently in grieving his brother’s death from AIDS and then his father’s death months later.

Familiar with themes of family rejection, Chris had also switched directions in his own career path. That he appeared to weather these storms, and in strong partnership with his wife Carroll, gave me the courage to disclose to him my mental health challenges. Both became mentors, allies and eventually dear friends we continue to see on our annual trips to Maine.

At times, my mask of functional normalcy slipped, and the truth of my past peeked out in the form of seemingly irrational fears and mood swings. Dave and other allies pleaded with me to stop living only halfway the truth of my past. Either I told my siblings and mother outright what was going on or I stop seeing them altogether.

I crafted a polite letter to Mother and my three siblings, requesting time away from them all. Given that Dad had been an attorney and that Lee and Tressie were attorneys, I noted in the letter that I was not undertaking any legal action. My letter neither accused anyone of anything, nor included verbiage of “abuse” or “incest.” I sent everyone the same letter via Certified Mail. Then I called Finch in search of an advocate, hoping that as the middle child she would mediate things. Big mistake.

Finch betrayed me immediately. Sounding the “family alarm” that I was sending a letter full of false accusations, the family lawyer mode seems to have gone into high gear. One of them decreed that a Certified letter constituted an “overt action” of legal portent, thus advised everyone to reject my letters. The letters from Tressie, Finch, and Mom came back to me unopened, the words “REFUSED” screaming in big letters across their envelopes. Further, Tressie left a message on our answering machine, threatening to make my life hell if I accused “her” mother of anything. She promised to tell everyone that I’d been in a psychiatric ward, and that she’d make me sorry for ever trying this stunt.

I went into exile from my family. My brother Lee came looking for me in Morgantown, hoping to have a conversation. Dave intervened and explained to Lee that I was too traumatized for any form of contact. He feared I was accusing our father, now long deceased, of molesting me. Lee reportedly felt relieved that this wasn’t the case; but I don’t think he pressed Dave for any further details.

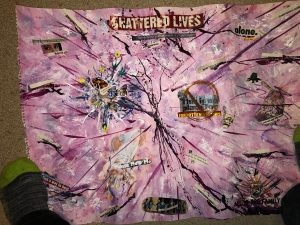

Rage surfaced to rival my fear. This time, my mirror was the music of Dmitri Shostakovich. To my archive of “therapeutic paintings,” I composed a collage of paint and newsprint from listening to the third movement of his Symphony No. 8. With the stereo set to loop, repeatedly on the third movement, a recording of the Leningrad Philharmonic playing it, I spent an afternoon hurling red and black paint across images and words I had torn from magazines and pasted onto the canvas.

My regular A.A. meetings in Morgantown were supplemented by weekly sessions with a new therapist. New layers of grief surfaced when I finally ripped out of my silence to send that letter to my family. The horrible, ugly, bloody mess I made didn’t seem at all worth it. I left my horn in its case for two years, mute and mumbling through my new path without a clue of its route.

Post-traumatic episodes, frequent during my time in Morgantown, did not deter me from pursuing my educational goals at WVU. Every flashback and migraine, every family threat (real or perceived) fueled my resolve to persevere. But I railed against various infirmities. I wanted to be someone beyond an identity as a “survivor of ___.”

Music Scholar

Early on in my degree program, I shared with my mentor Dr. Wilkinson an idea for a thesis. I loved Russian orchestral music, and I had lobbied successfully to continue my Russian language study to fulfill the compulsory foreign language credits for my degree. We had already traveled to Petrozavodsk and St. Petersburg once. Perhaps there was something about Russian music that I could address in a culminating research project, I suggested to him.

Dr. Wilkinson directed me to the university library and his spouse Carroll, whose expertise in information literacy proved an invaluable, positive force throughout my graduate experience. Her poise mixed with formidable intellect showed me a model of professionalism that seemed possible for me to one day emulate.

My mentor’s greatest gift as advisor on my thesis on Russian opera initially seemed the most perplexing: He knew nothing of my topic; he neither spoke nor read Russian; and he know little about Russian music beyond a standard undergraduate music history curriculum. The research I conducted would be fully mine. Before I had even penned a single sentence or pinpointed the thesis topic, he granted me both academic and creative credibility. I felt challenged – in a good way – to question the veracity of my negative self-image.

Dr. Wilkinson’s belief in my competencies remained unchanged despite the disclosure of my mental health issues. His mentorship on the tools of scholarship helped hone my cognitive functioning, which in turn strengthened my grasp on reality and pragmatic action. This helped tremendously in regulating my emotional overloads, so that I could balance more effectively the mind/body/feeling axes.

He also edited my prose with intense scrutiny. My papers were covered in his penciled scribbles pointing out every awkward expression, poor word choice, and poorly-organized paragraph. He explained the distinctions between set and found problems in research, keen to note where I had sloppily paraphrased ideas instead of querying their foundations.

One of the most useful skills I learned from Dr. Wilkinson were methods to organize a notebook of source materials during archival work. Additionally, I learned from him how to journal my writing sessions so that I could easily pick up the threads of my thinking after time away. Perhaps best of all, he granted me physical space to pace his office to talk through – and even argue – how best to unpack the complexities of research and writing. If anything fazed him about my eccentricities, he hid it well.

In clarifying the boundaries of his own expertise, my mentor gave me the intellectual space to explore and claim areas of my own scholarly authority. Having advised me through several trips to archives in the states in search of primary sources for final seminar projects, he pointed me toward Russia for my culminating degree research. “You’re the one with the language skills and contacts from your last trip. So, go back over there and find what you need for your thesis.”

Dave returned to Ghana when I returned to Petrozavodsk. Looking back, it seems clear how much Susan was a stabilizing force as I navigated my first international trip without Dave. And Dave clearly trusted her deeply to have let me go without him, given the emotional turmoil I was in over the family chaos. Of the many fond memories of shrieking laughter with Susan, I think my favorite is when we went through the litany of Russian singular and plural noun endings while spinning in circles on a rickety elevator in our St. Petersburg hostel. Or maybe it’s the hours we spent using a YakBack to record our altered voices. Or the whole bag of Oreos we saved to binge on the last week of camp.

I hope I always remember that dazzlingly brilliant moment, on the train from Petrozavodsk to St. Petersburg, when I realized how utterly alone I was. Dave was in Ghana conducting his own research. We could not reach each other by phone or cable. Susan and the rest of the student travel group had departed for Moscow. I sat on my suitcase beneath the bunk, just few hundred rubles in my passport pouch. My Russian was credible enough in basic conversation, or to inquire about directions or menus or money, read signage and newspapers.

No one, not even my husband, had any idea of my whereabouts. Sweet Jesus, but I was alive and kicking!

Feeling fully in command of my own destiny marked a turning point in my healing. Upon the successful defense of my thesis from that research abroad (“Re-thinking musical nationalism: Russian opera in the eighteenth century”), my mentor acknowledged the significance of this accomplishment in light of all the baggage I had carried alongside my studies.

Chris and Carroll had watched me succumb to paralyzing fear when I thought my family was headed to West Virginia to hurt me. The two of them had watched me regress, on more than one occasion, into a confused, vulnerable child talking about things only I could see. And yet, they remained steadfast in their belief that I was sane, capable, and supremely qualified to join the ranks of academic scholars.

Graduate studies aim to instill reasoned, disciplined methods of critical thinking that can support competent functioning in all areas of life. I emerged from my second master’s program with a much more developed and active sense of resilience. The survival instinct that had steered my undergraduate and first graduate experiences had been transformed into an awareness of how my distress and a desire to respond more pro-actively. I could speak another language, I had conducted research in a foreign country, and I had crafted a well-written persuasive thesis on an engaging topic within the discipline of music history. No one could ever take that away from me.

Modulating Into a New Key

Finally, I had accomplished more than just surviving bad things. Sobriety had launched a new trajectory, but I had made the commitment to forge new routes beyond survival. I was going to thrive!

The hard, diligent self-assessment required to live sober had gradually changed my default mode of emotional isolationism. Alcoholics in recovery learn to helped each other by practicing brutal honesty – tough love – to prevent drinking relapses. Unearthing the next of healing had required hospitalization for suicidal depression. I appreciated the skilled intervention of psychotherapists who helped me develop an effective set of responses to manage flashbacks and depressive episodes.

Asking for help from others had not, as my family warned, produced an infantile dependency on others. Instead, I discovered tremendous benefits by learning different perspective from others. It began to dawn on me that real, whole strength – the stuff of resilience – was not defined by either a stoic endurance of mistreatment or an exiled sense of martyrdom. It wasn’t all up to me to figure out everything for myself.

Returning to Duluth at the close of our graduate studies in West Virginia, I felt a keen sense of the yin and yang between my academic progress and my post-traumatic progress. I loathed the emotional drag of memories demanding my attention. They seemed to conspire to derail my newfound strength of identity. I feared the intense peaks of rage building toward my mother, sisters, and anyone blocking my paths forward.

My second master’s degree pivoted me toward doctoral studies in musicology. I had been accepted into the PhD program at the University of Minnesota. My plan was to rent a dorm room on campus and drive the two hours from Duluth the night before scheduled course seminars. The musicians of Klassic Retro had emigrated to the United States, and Sasha and Olga Chernyshev were now in a position to help me as I had once helped them. They introduced me to Gladys and Roger Reiling, who knew the trio from their second tour.

Gladys, a librarian for Ramsey County, met Sergei from the trio when he strolled into her library one day looking for resources. The uncanny coincidence of our mutual friendships with Klassic Retro formed an instant bond, as well as a place to stay. For the duration of my studies, the Reilings opened their home to me.

Many enlightening conversations, new friendships with additional international travelers, and even some impromptu concerts took place at the Reiling home. Their beautiful residence in Roseville features a central atrium with a piano (the rug beneath it aptly named “Rachmaninoff”). The Reilings proved to be staunch allies when all of my transactional strategies to control things utterly failed.